THE DISTRIBUTION ARTIST

December 19, 2004

By Lynn Hirschberg

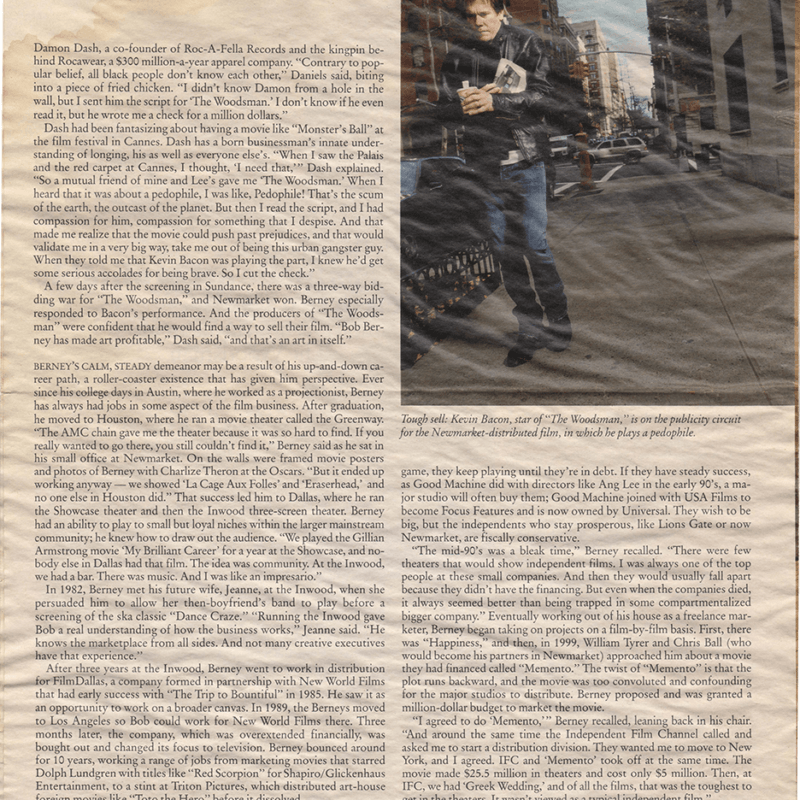

On Nov. 23, the 3.30 p.m. marketing meeting of Newmarket Films was devoted to the selling strategy for a movie called “The Woodsman.” The film, which opens in New York on Dec. 24, stars Kevin Bacon as a pedophile who has just been released from ·ail. While all kinds of mental illness and acts of extreme violence can be intriguing to audiences, the story of a deeply flawed but sympathetic man who is attracted to very young girls does not lend itself to the sort of film, however worthy, at any studio would be likely to finance or distribute, especially at Christmas.

Which is exactly why Bob Berney, the president of Newmarket Films, is releasing it then. In the last three years, first at IFC Films and, or the last 28 months, at Newmarket, Berney has proved to be remarkably perceptive about the tastes of the moviegoing public. Against all odds, he masterminded the distribution of “My Big Fat Greek Wedding,” which had no stars and was considered too mainstream by most independents, and “The Passion of the Christ,” which was rejected by many studios. Those films have earned, respectively, $241.4 million and $370.3 million in the United States, making them by a large margin the two most successful independent films of all time. In 2003, Newmarket released “Monster,” starring Charlize Theron, who gained 30 pounds and wore heavy makeup to play the murderer Aileen Wuornos. “We opened our serial killer, lesbian-prostitute film on Christmas Eve in Manhattan,” Berney said, linking “Monster” to “The Woodsman.” “And it worked.” Theron won practically every award invented, including an Oscar, and the movie, which cost roughly $8 million, went on to make $34.5 million. Newmarket Films and its “genius” (as Theron called Berney) were suddenly the biggest success story in the movie business.

But “Monster” falls into a safer, more familiar cinematic genre than “The Woodsman.” There are protagonists and subject matters that are dark and complex in an interesting way, but pedophilia is too unsettling for most audiences. “Controversy can help a film,” Berney said before the marketing meeting began_”. But I do think this is the one subject that has to be explained. Controversy only works when the controversy is not uncomfortable for people. Pedophilia is not an easily discussed subject.”

Berney sat down at Newmarket’s modern conference table in a windowless room in the company’s offices near Rockefeller Center. He is an unusually calm man (“It takes me a long time to get angry,” he said, “and, by then, it’s usually too late”) with a soft voice that has a slight drawl, left over from his childhood in Oklahoma. He is a careful dresser and was wearing a white button-down shirt with a subtly woven pinstripe and navy pants. Although he is 51, he has an ageless face that is hard to read. He’s a little opaque, a little blank, which is particularly unusual in the realm of movie moguldom. There is no bombast with Berney, no razzle-dazzle. His effectiveness, unlike Harvey Weinstein’s at Miramax, is not tied to personal showmanship. And yet when Berney talks about “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” the Mexican road movie that he released unrated, or “Whale Rider,” the New Zealand film that nearly every distributor passed on and he made a success, his eyes take on a certain gleeful ferocity. “Bob is kind of an enigma,” Kevin Bacon said, “but I think that’s part of why he’s effective. I wouldn’t want to play poker with him. He’s easy to underestimate and very hard to read. Those traits usually mean you win.”

The extraordinary success of Berney and Newmarket Films (which is owned by Berney and two British financiers, William Tyrer and Chris Ball, who live in Los Angeles) has not gone unnoticed by the studios. This fall, Tom Freston, co-president of Viacom, which owns Paramount, approached Newmarket about purchasing it. The arrangement would be similar to the original deal between Miramax and Disney. Before that relationship soured, Miramax was the autonomous independent wing of the Disney studios, releasing films like “Pulp Fiction” that were quirkier and more daring than its parent studio’s choices. “In the past few years, independent films have become big business,” says Sherry Lansing, the outgoing chairwoman of Paramount. “They are not just quality films that you stick in your release schedule like filler. And Tom Freston wants to release movies he wants to see. Most of the time, those films would come from the ranks of the independents, like Newmarket.”

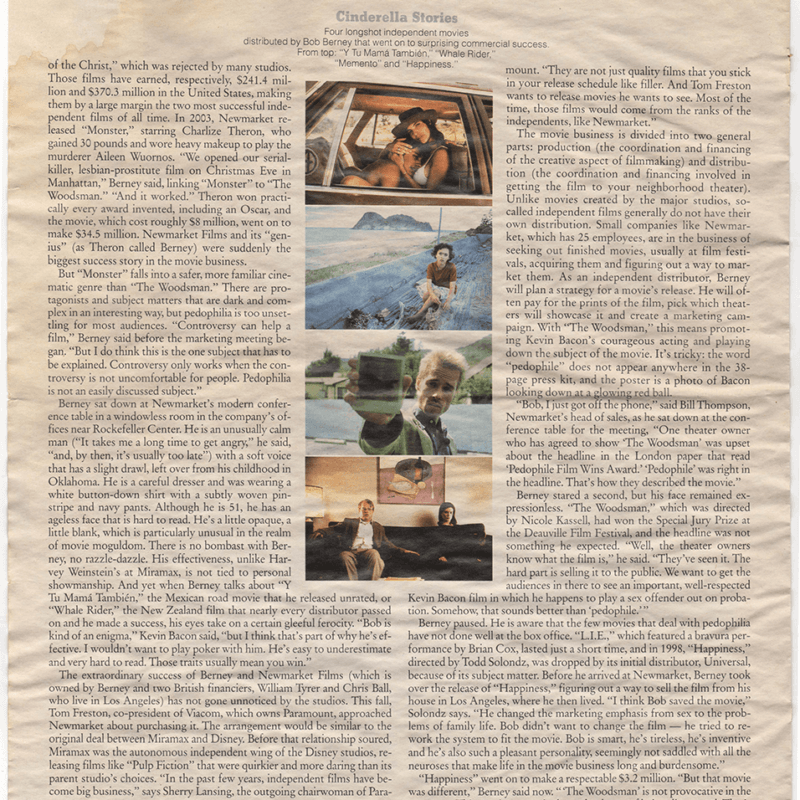

The movie business is divided into two general parts: production (the coordination and financing of the creative aspect of filmmaking) and distribution (the coordination and financing involved in getting the film to your neighborhood theater). Unlike movies created by the major studios, socalled independent films generally do not have their ov.rn distribution. Small companies like ewmarket, which has 25 employees, are in the business of seeking out finished movies, usually at film festivals, acquiring them and figuring out a way to market them. As an independent distributor, Berney will plan a strategy for a movie’s release. He will often pay for the prints of the film, pick which theaters · will showcase it and create a marketing campaign. With “The Woodsman,” this means promoting Kevin Bacon’s courageous acting and playing down the subject of the movie. It’s tricky: the word “pedophile” does not appear anywhere in the 38- page press kit, and the poster is a photo of Bacon looking down at a little red ball.

“Bob, I just got off the phone,” said Bill Thompson, Newmarket’s head of sales, as he sat down at the conference table for the meeting, “One theater owner who has agreed to show ‘The Woodsman’ was upset about the headline in the London paper that read ‘Pedophile Film Wins Award.’ ‘Pedophile’ was right in the headline. That’s how they described the movie.”

Berney stared a second, but his face remained expressionless. “The Woodsman,” which was directed by Nicole Kassell, had won the Special Jury Prize at the Deauville Film Festival, and the headline was not something he expected. “Well, the theater owners know what the film is,” he said. “They’ve seen it. The hard part is selling it to the public. We want to get the audiences in there to see an important, well-respected Kevin Bacon film in which he happens to play a sex offender out on probation.

Somehow, that sounds better than ‘pedophile.'”

Berney paused. He is aware that the few movies that deal with pedophilia have not done well at the box office. “L.I.E.,” which featured a bravura performance by Brian Cox, lasted just a short time, and in 1998, “Happiness,” directed by Todd Solon dz, was dropped by its initial distributor, Universal, because of its subject matter. Before he arrived at Newmarket, Berney took over the release of “Happiness,” figuring out a way to sell the film from his house in Los Angeles, where he then lived. “I think Bob saved the movie,” Solondz says. “He changed the marketing emphasis from sex to the problems of family life. Bob didn’t want to change the film – he tried to rework the system to fit the movie. Bob is smart, he’s tireless, he’s inventive and he’s also such a pleasant personality, seemingly not saddled with all the neuroses that make ]if e in the movie business long and burdensome.”

“Happiness” went on to make a respectable 53.2 million. “But that movie was different,” Berney said now. “‘The Woodsman’ is not provocative in the same way. This movie, to me, is about the drama of being discovered. That’s what audiences respond to. Everyone has secrets, everyone has shame.”

By now, seven members of the Newmarket staff had gathered around the conference table. Berney has complete faith in the film’s worth, and his quiet, steady belief was contagious. “I guess it sounds arrogant,” Berney had said, “but I am surprised when audiences don’t see what I see in the movies. With ‘Passion of the Christ,’ people were doubtful. We released it on Feb. 25, Ash Wednesday. We put together a plan, which was to go to 2,000 screens right away. That was the riskiest move we ever made as a company. The concern was that the movie might turn out to have a limited appeal and no one would go. If that had happened, we’d be out of money. But Mel” – Mel Gibson, who produced and directed the film – “had always wanted to release it that way, and he liked our plan.”

Berney paused again. He looked down at a mock-up of an ad for “The Woodsman.” He updates and changes the ads for his movies constantly – the first “Woodsman” ad in Variety didn’t even state the title of the film. “More mystery is always good,” he said.

“The Passion of the Christ,” like many of Berney’s films, was helped by positiYe word of mouth and a certain notoriety. Since he has never relied on blanket TV advertising, Berney supports his films through alternative methods, like film festivals, special screenings, radio promotions and Internet marketing. As with “Monster,” most of the campaign for “The Wood man” revolves around its star. “Following Bob’s plan, I’m doing something connected to this movie every day for three straight months,” Kevin Bacon would later tell me. “And that’s until release. Who knows what Bob has in store for me if we get nominations for the Golden Globes or Academy Awards?”

“Let’s see the trailer,” Berney said, as the meeting wound down. Mary Ann Hult, Newmarket’s director of publicity, turned on the TY, which sat next to a ha-If-eaten gift basket of cheese and crackers. The coming-attraction spot was, true to Berney’s vision, all about Bacon’s character having a secret. He has been in jail for something terrible, but he doesn’t say what. He’s talking about his past in a cloudy manner. He’s withdrawn and troubled and finally, compelling. The last line of the trailer – ”I’m not a monster” – is chilling and provocative.

“It’s good,” Berney said. He asked to see another version of the same spot. “I would see that movie,” he said quietly to himself.

There’s a sense of romance in the way that Bob Berney talks about seeing his movies for the first time. He usually encounters them at a screening at a festival with other potential distributors. “I’m always looking for something I can’t predict,” Berney said, over fish and chips at an Irish restaurant around the corner from his office. “It’s a little like falling in love – you couldn’t imagine how this film hadn’t existed in your life before, and then, it’s there.”

He had that feeling when he first saw “Y Tu Mama Tambien” at Cannes. “It reminded me of my college days at the University of Texas at Austin,” he said, “and I thought it would also appeal to the Latin audience.” And he had the feeling again when he saw ”Whale Rider,” the story of a Maori girl, played by the 11-year-old Keisha Castle-Hughes. Improbably, Hughes was nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award for her performance. The success of “Whale Rider,” which cost $4.5 million and went on to make $20.8 million, is perhaps Berney’s most impressive triumph. The film is foreign, with no stars and an unfamiliar subject. “When I was a kid,” Solondz said, “we called movies like ‘Whale Rider’ ‘adventure films for children.’ Bob made that genre appealing again.”

“‘Whale Rider’ was my first acquisition at Newmarket,” Berney said, as he ate a French fry. “We came out in June of 2003 and we played all summer. Part of what helped us is 30-screen theaters in New York City like the Empire in Times Square. More screens are good for independent films – the theaters need films, and the exhibitors leave them in the theaters longer. They don’t define movies as independent or studio – they’re just looking for something that works. I found this out with ‘Whale Rider’ as well as with ‘Passion of the Christ.’ The most successful screen for ‘Passion’ was at the Empire in Manhattan. That theater attracted the Latin audience, which was huge for that movie. It did better at the Empire than anywhere else in the country, even though it was widely believed that urban audiences, especially in New York City, wouldn’t respond to the film.”

When Berney saw “The Woodsman” at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2004, he was immediately fascinated. At the time, his life was hectic – Newmarket was working on the Oscar campaigns for “Monster” and “Whale Rider,” and it was also getting ready to release “The Passion of the Christ” on 2,000 screens in a month. “We were panicked,” he explained. “The studios have three and four hundred people doing what we did with a staff of 18. It was hard to know if we could even get the prints of ‘Passion’ necessary for all the screens. Mel wasn’t finished with the film, and we were making prints in Rome, Canada and L.A. The exhibitors were betting against us. It was down to the wire and we made it.”

Lee Daniels, the producer of “The Woodsman,” said: “I knew about Bob Berney and Newmarket and ‘The Passion of the Christ.’ And I thought, Why is he interested in ‘The Woodsman’? I mean, it’s not like everyone was bidding for this movie. After our first screening at Sundance, it took two days for the phones to start ringing. In general, people weren’t clapping at the end of the film. It’s the subject. I guess I’m naiveI thought we’d win Sundance, but we lost, and we left without a distributor. They were only thinking of the marketability. I said, Let’s make history, guys – trust me. They still said no. Except for my Bob.”

Daniels related this over lunch in the cafeteria of the United House of Prayer for All People, a religious meeting hall near his offices in Harlem. An openly emotional man with an expressive face and a mane of electric dreadlocks, Daniels had success a couple of years before with “Monster’s Ball,” his debut as a producer. Halle Berry won an Oscar for her portrayal of a beaten-down Southern woman in that film, and the movie earned several times its production cost of $4 million.

Still, Daniels could not get the studios to invest in “The Woodsman.” Eventually, he persuaded Brook Lenfest, a Philadelphia businessman, to invest $1 million, and when he was in Cannes for “Monster’s Ball,” he met Damon Dash, a co-founder of Roe-A-Fella Records and the kingpin behind Rocawear, a $300 million-a-year apparel company. “Contrary to popular belief, all black people don’t know each other,” Daniels said, biting into a piece of fried chicken. “I didn’t know Damon from a hole in the wall, but I sent him the script for ‘The Woodsman.’ I don’t know if he even read it, but he wrote me a check for a million dollars.”

Dash had been fantasizing about having a movie like “Monster’s Ball” at the film festival in Cannes. Dash has a born businessman’s innate understanding of longing, his as well as everyone else’s. “When I saw the Palais and the red carpet at Cannes, I thought, ‘I need that,”‘ Dash explained. “So a mutual friend of mine and Lee’s gave me ‘The Woodsman.’ When I heard that it was about a pedophile, I was like, Pedophile! That’s the scum of the earth, the outcast of the planet. But then I read the script, and I had compassion for him, compassion for something that I despise. And that made me realize that the movie could push past prejudices, and that would validate me in a very big way, take me out of being this urban gangster guy. When they told me that Kevin Bacon was playing the part, I knew he’d get some serious accolades for being brave. So I cut the check.”

A few days after the screening in Sundance, there was a three-way bidding war for “The Woodsman,” and Newmarket won. Berney especially responded to Bacon’s performance. And the producers of “The Woodsman” were confident that he would find a way to sell their film. “Bob Berney has made art profitable,” Dash said, “and that’s an art in itself.”

BERNEY’S CALM, STEADY demeanor may be a result of his up-and-down career path, a roller-coaster existence that has given him perspective. Ever since his college days in Austin, where he worked as a projectionist, Berney has always had jobs in some aspect of the film business. After graduation, he moved to Houston, where he ran a movie theater called the Greenway. “The AMC chain gave me the theater because it was so hard to find. If you really wanted to go there, you still couldn’t find it,” Berney said as he sat in his small office at Newmarket. On the walls were framed movie posters and photos of Berney with Charlize Theron at the Oscars. “But it ended up working anyway- we showed ‘La Cage Aux Foiles’ and ‘Eraserhead,’ and no one else in Houston did.” That success led him to Dallas, where he ran the Showcase theater and then the Inwood three-screen theater. Berney had an ability to play to small but loyal niches within the larger mainstream community; he knew how to draw out the audience. “We played the Gillian Armstrong movie ‘My Brilliant Career’ for a year at the Showcase, and nobody else in Dallas had that film. The idea was community. At the Inwood, we had a bar. There was music. And I was like an impresario.”

In 1982, Berney met his future wife, Jeanne, at the Inwood, when she persuaded him to allow her then-boyfriend’s band to play before a screening of the ska classic “Dance Craze.” “Running the Inwood gave Bob a real understanding of how the business works,” Jeanne said. “He knows the marketplace from all sides. And not many creative executives have that experience.”

After three years at the Inwood, Berney went to work in distribution for FilmDallas, a company formed in partnership with New World Films that had early success with “The Trip to Bountiful” in 1985. He saw it as an opportunity to work on a broader canvas. In 1989, the Berneys moved to Los Angeles so Bob could work for New World Films there. Three months later, the company, which was overextended financially, was bought out and changed its focus to television. Berney bounced around for 10 years, working a range of jobs from marketing movies that starred Dolph Lundgren with titles like “Red Scorpion” for Shapiro/Glickenhaus Entertainment, to a stint at Triton Pictures, which distributed art-house foreign movies like “Toto the Hero” before it dissolved.

There were other jobs, too, at other companies that no longer exist. Independent film entities are known for their boom-and-bust sagas. Often, a hit or two makes them flush and then, like a gambler who can’t leave the as Good Machine did with directors like Ang Lee in the early 90’s, a major studio will often buy them; Good Machine joined with USA Films to become Focus Features and is now owned by Universal. They wish to be big, but the independents who stay prosperous, like Lions Gate or now Newmarket, are fiscally conservative.

“The mid-90’s was a bleak time,” Berney recalled. “There were few theaters that would show independent films. I was always one of the top people at these small companies. And then they would usually fall apart because they didn’t have the financing. But even when the companies died, it always seemed better than being trapped in some compartmentalized bigger company.” Eventually working out of his house as a freelance marketer, Berney began taking on projects on a film-by-film basis. First, there was “Happiness,” and then, in 1999, William Tyrer and Chris Ball (who would become his partners in Newmarket) approached him about a movie they had financed called “Memento.” The twist of “Memento” is that the plot runs backward, and the movie was too convoluted and confounding for the major studios to distribute. Berney proposed and was granted a million-dollar budget to market the movie.

“I agreed to do ‘Memento,”‘ Berney recalled, leaning back in his chair. “And around the same time the Independent Film Channel called and asked me to start a distribution division. They wanted me to move to New York, and I agreed. IFC and ‘Memento’ took off at the same time. The movie made $25.5 million in theaters and cost only $5 million. Then, at IFC, we had ‘Greek Wedding,’ and of all the films, that was the toughest to get in the theaters. It wasn’t viewed as a typical independent film.”

As usual, Berney tailored his distribution approach to the film. He suspected “Greek Wedding” would not prosper in a wide release. “We kept it small,” he said. “The tendency would be to go as big as possible, and I didn’t want to do that.” The strategy worked: a film that might have seemed common instead felt special. Berney also enlisted the help of Jeanne, an experienced movie publicist who has worked on many of his movies.

In the summer of 2002, after his rapid success with “Y Tu Mama Tambien” and “Greek Wedding,” Berney abruptly left IFC. “It was a scandal,” Berney admitted. “But Newmarket presented a great opportunity.” He had finally found a company that would not combust.

As film financiers, Berney’s partners at Newmarket had a relationship with Icon, Mel Gibson’s production company. They invested in Gibson’s version of “Hamlet.” When 20th Century Fox, which had rights on the film, decided not to distribute “The Passion of the Christ” in theaters (they found it too controversial), Newmarket was a top contender. Gibson may have also liked that Berney was a practicing Catholic and that his two sons (Sean and Liam, now 15 and 12) had gone to St. Paul the Apostle, a Catholic school in West Los Angeles. “I never told Mel that I was religious,” Berney said. “But they’re like the C.I.A. over at Icon – they just know everything.”

Unlike most independents, Newmarket has always been careful in its business deals. It has missed opportunities in the interest of caution. It could have invested in the production of ”Monster” in its early stages but declined to do so, thereby forfeiting a larger share of the movie’s eventual profits. And on “Passion,” Newmarket’s distribution fee is under 12 percent. Had the company offered to pay for the prints of the film or shoulder the cost of advertising, it could have negotiated a much greater return on its investment. “The Passion of the Christ” may have catapulted Newmarket, but it did not make the company super rich, which is, all things considered, O.K. with Berney. He has seen indies soar and crash, and he’d rather be careful than lose everything.

Newmarket is concentrating on consistency. While it has had some flops – “Stander,” an intriguing movie about a South African cop turned bank robber, lasted only one week last summer in New York – it is not aiming for a high-volume, shoot-the-moon existence. If Newmarket is bought by Paramount in the coming months, it will most likely become Paramount’s answer to Fox Searchlight Pictures. Currently the most consistently interesting specialty division of a studio, Fox Searchlight has excelled at acquisitions (“Napoleon Dynamite”) and production (“Sideways”).

“It all comes down to what choices you make,” Berney said. “I know every movie-theater owner in the country. I like that world, and I spend a lot of time talking to them. They spend a lot of their time trying to figure out the audience. And they all want good movies.” Berney smiled halfway. His desk was covered with “Woodsman” stuff – ads and reviews and a copy of the poster with the strange glowing orb. “You can’t give up on the audience,” he said. “You have to believe they want to see something interesting.”

On a cold, clear night in early December, Bob and Jeanne Berney made their way into the IFP Gotham Awards, New York’s annual celebration of independent films, at Chelsea Piers. They eschewed the red carpet and headed straight into the packed cocktail reception. “You’re a god in Texas,” screamed Jack Foley, the president of distribution at Focus Features. Like nearly everyone here, Foley has known the Berneys “forever” and embraced Bob in a bear hug. “He knew me at the Inwood,” Berney explained. Because Jeanne has worked as a publicist, she greeted almost as many guests as her husband. The couple were like pinballs, bumping into one old friend or business associate ( or both) after another.

Although he clearly enjoyed the social whirl, Berney said the main point of the evening was to generate attention for “The Woodsman.” The day before, the IFP Independent Spirit Award nominations were announced, and “The Woodsman” garnered three, including best male lead for Bacon. But the National Board of Review had not named the film as one of its Top 10. “Awards and mentions are important,” Berney said between hugs. “But most of all, it’s important to generate conversation.”

Tonight, “The Woodsman” was up for two awards – Breakthrough Actor and Breakthrough Director. Bacon and his wife, the actress Kyra Sedgwick (who plays his love interest in “The Woodsman”), were each presenting an award, and Newmarket and Lee Daniels had both bought tables. After an hour of cocktails, the crowd slowly moved into the dining room. The “Woodsman” tables were next to the “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” table, and Jim Carrey posed for snapshots.

Soon, Daniels arrived, and then Damon Dash and the actor and rapper Mos Def, who was nominated for his subtle performance in “The Woodsman.” “Everybody is asking me for money,” Dash said. He had, of course, walked the red carpet. He was, as he often is, followed around by his own camera crew. ‘Tm not really making a movie,” he explained. “It’s more like a reality show.” When he visited the set of “The Woodsman,” Dash arrived by helicopter, as always with entourage and film crew in tow, for the most wrenching scene in the film, in which Bacon’s character relapses and tries to seduce an 11-year-old girl.

Hours later, Daniels was disappointed – “The Woodsman” lost to HBO Films’ “Maria Full of Grace” in both categories. “How could we lose?” he roared. “I’ve seen both movies.” Berney remained sanguine. “The important thing,” he repeated, “is exposure. Kyra and Kevin were presenters, the movie was mentioned all night and we were a big presence.” Daniels, who is as grand in his presentation as Berney is modest, stared a second. “You so understand my journey,” Daniels said, finally, as he hugged Berney. He was soothed.

After another attempt to leave (more hugs, another “You’re a god in Texas”), the Berneys found their car and went back to the Soho House hotel. They live in suburban Bronxville now, Jeanne has taken time off to be with their kids and Bob and Newmarket might soon be bought by a big studio; their fortunes have shifted, probably for good. “I’m happy for the success,” Berney said a few days ago in his office, “but I’ve-learned that you have to concentrate on the current film, not revel in your past triumphs.” He paused. “I’ve always preferred coming at things from another angle.”