NEWS ARCHIVE

Bob Berney on the New Landscape for Theatrical Distribution

By Daniel Loria

Read at boxofficepro.com

In this week’s episode of The Boxoffice Podcast, distribution veteran Bob Berney joins Boxoffice Pro editorial director Daniel Loria in a conversation about the seismic changes affecting theatrical distribution and exhibition as audiences return to theaters.

After starting his career programming independent and specialty films for movie theaters in Texas, Berney made the jump to distribution and went on to release some of the most successful arthouse titles of the last three decades. Roles at IFC Films (Y TU MAMÁ TAMBIEN, MY BIG FAT GREEK WEDDING), Newmarket Films (THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST, MONSTER, WHALE RIDER), and FilmDistrict (INSIDIOUS, DRIVE) preceded his appointment as head of marketing and distribution at Amazon Studios in 2015. During his four years at Amazon, Berney helped launch the tech giant’s foray into theatrical distribution with a strategy that embraced traditional theatrical releases and promoted a diverse slate of crossover independent titles like MANCHESTER BY THE SEA and THE BIG SICK.

Berney left Amazon to relaunch his own distribution company, Picturehouse, in 2019. In this interview, Berney shares his insights on the current volatility affecting the theatrical market as streaming companies make a play for big movies and major franchises at the multiplex, while specialty players learn to adapt to a market without the influence of the film festival circuit.

Like most movies of 2020, FATIMA has had anything but a traditional release.

Originally intended to hit theaters April 24 of last year, the historical drama chronicling the 1917 Marian apparitions to three Portuguese children experienced delay upon delay due to theater closures amid the COVID-19 pandemic. But next month, the film will finally have a major theatrical release when it opens in AMC theaters nationwide.

“I sometimes think this is Mary’s release, not ours,” said Jeanne Berney, chief operating officer of the film distribution company Picturehouse. To Jeanne and her husband Bob, Picturehouse’s CEO, the May 7-14 scheduled release, which coincides with Mother’s Day and the feast of Our Lady of Fatima, is nothing short of providential.

In a phone interview, the Berneys explained that Bob had been communicating with AMC last year in preparation for the film’s original release. But in light of the pandemic, Picturehouse had to change course. They settled for an August 28 “premium video on demand” release, a new pandemic-driven phenomenon that released the film digitally as well as in select independent theaters. Later, viewers could purchase the film online or on DVD, and starting in January, they could find it on Netflix.

Since its release, FATIMA has received a 94% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes and won the Family Award at this year’s Los Angeles Italia Film, Fashion, and Art Festival. It has also received endorsements from several bishops, as well as the official shrine of Fátima in Portugal.

But as restrictions have eased, the Berneys felt compelled to increase the film’s visibility. “I always felt like we never were able to really deliver that [release] in a theatrical way because of the pandemic,” said Bob, “so I really started thinking, with AMC’s support, that we could actually bring it back. The theaters have now opened … but there still aren’t a lot of movies yet to be released. The studios have been held back. So [AMC] loved the idea.”

According to the Berneys, bringing FATIMA to the big screen is important for the film itself and for audiences. “It’s a way not only to see how beautiful [the film] is, but also for people to experience a film like this together,” said Bob. “You do feel the power of it in the auditorium. It’s all great to watch it at home, but I think it is special to see it with people in a bigger auditorium.”

“[This is a way] for people to see the movie the way it was meant to be seen,” said Jeanne.

Depending on states’ COVID-related restrictions at the time of release, the film will show in up to 350 AMC theaters nationwide. To encourage audiences to get out to the theaters, Picturehouse and AMC agreed to set up the re-release as part of AMC’s “$5 Fan Faves” program, which brings previously released films back to the big screen. Tickets will remain at that price throughout the weeklong first run and the duration of its time in theaters, which will depend on its box office performance. The Berneys hope that the reduced price will motivate church groups, schools, and families to gather and see the film in theaters for several weeks.

“We can really give people all the reasons to come and see it,” said Jeanne. “The presentation, the price, the story, and the month of May being Mary’s month.”

After a year navigating the challenges of a global pandemic, the Berneys have found the film to be a source of consolation. “Particularly this past year, I think everyone has needed something to inspire them or to give them hope, and the movie does that,” said Bob. “I hope it also brings people back to their faith … or reaffirms it.”

Jeanne added that they envision the film inspiring dialogue between Catholics and people of another or no faith and bring a message of hope from over 100 years ago to the present day. “It’s an emotional, beautiful story,” she noted. “And this story is still relevant. It’s not a thing of the past.”

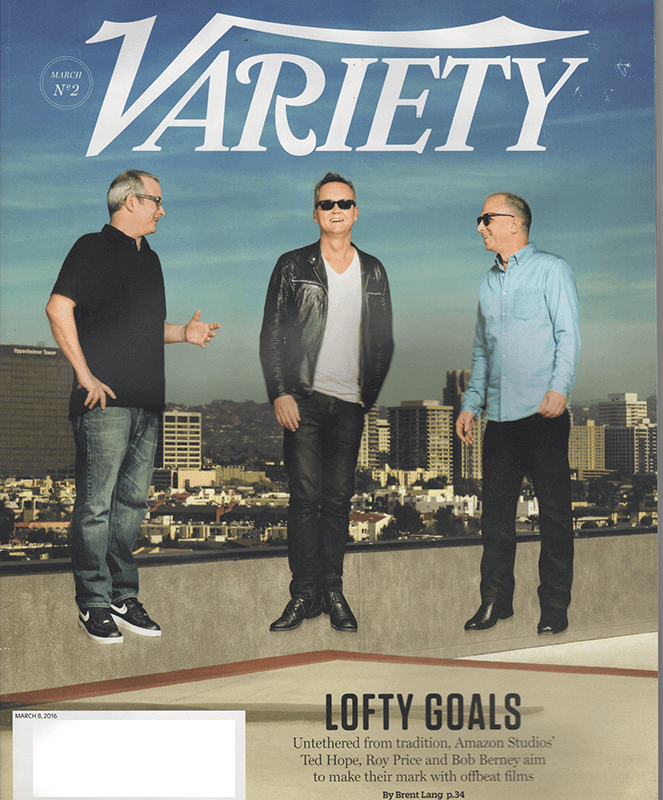

AMAZON STUDIO PLOTS ITS COURSE

March 8, 2016

By Brent Lang

As snow fell steadily, blanketing the mountainside town of Park City, the team from Amazon Studios huddled in a parking lot to discuss the movie that had just premiered at the Sundance Film Festival.

Moments before, the drama ‘Manchester by the Sea,’ a finely calibrated portrait of grief and loss, had received a standing ovation, triggering predictions on social media that the picture would be a major Oscar contender. As the credits rolled, potential buyers rushed to the exits. Amazon Studios chief Roy Price, who was stuck in the middle of a long row of moviegoers, had to vault over seats to get out of the packed theater.

“We were out afterward in the cold, shivering,” recalls Ted Hope, head of motion picture production at the company. “We were all agreeing on the same thing – that we saw something that doesn’t come around much.”

It was a crucial moment for Amazon. After largely sitting out the major festivals and markets, or falling short in its bid to land acclaimed films like ‘Brooklyn,’ the movie arm of the Seattle-based streaming giant needed to make a splash. Just before 2 a.m., the Amazon executives scrunched into a sports utility vehicle to make their way up a Park City mountain, where the “Manchester” creative team and a phalanx of agents were hearing pitches from the likes of Sony, Universal, Fox and Lionsgate.

“The car is swerving,” says Hope. “I’m going out on a mountain ledge to risk my life to buy this film. You can’t even see. They don’t make windshield wipers fast enough to go back and forth for the snow.”

Hours of haggling and $10 million later, Amazon had nabbed its prize. It would leave Sundance with four acquired films, including the quirky comedy “Wiener-Dog”, the acclaimed documentaries “Gleason,” a look at an NFL star battling ALS, and ”Author, The JT Leroy Story,’ an examination of a literary fabulist.

“It’s like the T-1000,’ says Graham Taylor, head of global finance and distribution at WME, the agency that sold Amazon most of its Sundance purchases, referring to the next-gen Terminator. “They’re getting faster, smarter, more operationally nimble.”

Amazon’s buying blitz broadcast the company’s ambitions to carve out a niche as a destination for prestige films at a time when major studios are focused on big-budget spectacles. In the process, Amazon is upending the independent film space. Along with Netflix, which paid top price last year for “Beasts of No Nation,” and recently bid $20 million but failed to land slave drama “The Birth of a Nation,” Amazon is shelling out the kind of money that would be ruinous for a Sony Pictures Classics or A24. The gap between these giants and smaller, pluckier players will only widen as other tech titans such as Apple and Hulu dive into the original content business.

”Amazon has a track record of going into various industries and blowing away the competition,” says Will Richmond, an analyst at VideoNuze.

While the primary source of corporate parent Amazon’s business is e-commerce and shipping, there’s a reason the company has intensified its push into digital video, analysts say. Just as Amazon foresaw that the rise of the Internet would fracture the retail business, new technology is now splintering the entertainment landscape. The ground is shifting under the broadcast and cable industries as audiences move online, and there’s an opportunity for aggressive players to capture this migrating consumer base.

“The state of play in the video industry is very unsettled, and among large companies like Amazon, Google, Apple and Netflix, there’s very much a land-rush mentality,” Richmond says.

But the Amazon model differs from that of Netflix. Whereas Netflix debuts its films on its streaming service, only grudgingly agreeing to screen them in theaters when it needs to qualify for awards, Amazon adheres to a more traditional distribution strategy. It partners with indie distributors, such as Roadside or Bleecker Street, to release movies in theaters, and then makes them available through its Prime subscription service in what is traditionally known as the pay-television window – the time when a film would run on an HBO or Showtime. Every Amazon film will get a theatrical release, but that time period can range from an abbreviated 30 days in cinemas to a standard 90 days.

This model has won the company the loyalty of filmmakers such as Spike Lee, whose ‘Chi-Raq,’ a look at gang violence in Chicago, became Amazon’s first theatrical release last December.

“Maybe I’m old-fashioned, but I like my films to be in a theater first before people watch it on an iPhone,” says Lee.

Months after fleeing the snow drifts of Park City, Price sat in a Midtown Manhattan restaurant, sipping tea while sketching out his ambitious plans to make Amazon a force in movies, just as it is in television. He wants the company to release between 10 and 12 films a year, with budgets ranging from $5 million to $40 million. Price hopes the studio will become the kind of standard bearer for quality that Paramount Pictures was under Robert Evans in the 1970s, a time that saw the release of “The Godfather” and “Chinatown,’ and that Miramax was in its ’90s “Pulp Fiction” heyday.

Whereas Netflix has signed deals with the likes of Adam Sandler and Pee Wee Herman in the hopes of reaching the broadest possible audience, Amazon has moved in a quirkier direction. It’s backing projects from Whit Stillman (“Love & Friendship”), Todd Solondz (“Wiener-Dog”), and an untitled film from Woody Allen – directors who are admired by critics, but have limited commercial appeal.

“‘Mall Cop’ is a very funny film, and someone should make it, but that’s not what we’re doing,” says Price, whose casual look is often carried off with a white T-shirt, black leather jacket and sneakers. “We want to work with visionary film makers who are making interesting films that you’re still going to be talking about in three years,’

That’s how Amazon has made waves on the television side of the business – by rolling the dice on edgy and offbeat original works such as “Transparent,” a comedy about a family dealing with a transgender parent, and ‘Mozart in the Jungle,’ a dramedy set in the world of classical music. They’re the kinds of projects that would struggle to get a pilot order or would be, in the words of “Transparent” creator Jill Soloway, so “bologna-fied” that they would lose their distinctive qualities.

“So often the tone is the first thing to leak out,” Soloway says. “It’s the victim of all the smallish political necessities that go with working with networks. There are all these people involved with every decision, and they’re telling you things need to be brighter, shinier, more about wish fulfillment, and the women need to be prettier.”

At Amazon, Soloway says, the approach is more streamlined, with fewer layers of bureaucracy to navigate. It’s been smart for business. Giving their showrunners more freedom has resulted in Emmys and Golden Globes.

Amazon hopes to become a destination for the same kind of idiosyncratic artists on the film side, who may find themselves slightly to the left of mainstream tastes. To help realize his movie dreams, Price has tapped two film executives who had a front-row seat during the independent film revolution of the 1990s, Hope, producer of “The Ice Storm” and “American Splendor,’ and Bob Berney, former CEO of indie film distributor Picturehouse and the marketing guru behind “The Passion of the Christ” and “My Big Fat Greek Wedding,’ The hirings sent a clear message to filmmakers toiling in the arthouse scene.

“I don’t know who could have brought more credibility and knowledge and prestige to what they’re doing,” Stillman says. “There are not that many great homes for our kind of films, so it was hugely reassuring that this would be a place that could catapult them into the marketplace in the right way.”

For Hope, who was hired in January 2015, the call came when he was feeling disillusioned about the state of the movie business. In 2012, he took a job at the San Francisco Film Society, hoping to transform the nonprofit into an incubator for movies. But disagreements about funding led to his resignation the following year, and in a blistering op-ed on his website, he wrote that after working on more than 50 films, he was no longer interested in producing for a living. The economic model was collapsing, he wrote, and cobbling together financing required too many sacrifices – cuts in budgets and development time, and casting concessions to appease the money.

“I want to make films that lift the world and our culture higher – and our current way of doing things does just the opposite,” Hope wrote.

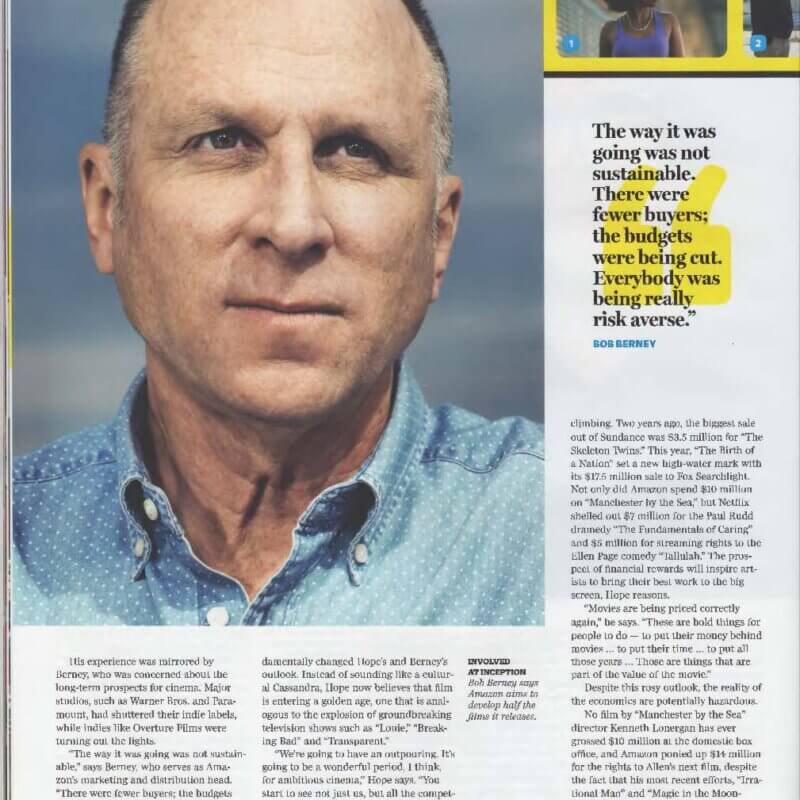

His experience was mirrored by Berney, who was concerned about the long-term prospects for cinema. Major studios, such as Warner Bros. and Paramount, had shuttered their indie labels, while indies like Overture Films were turning out the lights.

“The way it was going was not sustainable,” says Berney, who serves as Amazon’s marketing and distribution head. “There were fewer buyers, the budgets were being cut. Everybody was being really risk averse.”

Working at Amazon, which has the cash and the mandate to back films that aren’t scrubbed of their edges, has fun damentally changed Hope’s and Berney’s outlook. Instead of sounding like a cultural Cassandra, Hope now believes that film is entering a golden age, one that is analogous to the explosion of groundbreaking television shows such as “Louie,’ “Breaking Bad” and “Transparent.”

“We’re going to have an outpouring. It’s going to be a wonderful period, I think, for ambitious cinema,” Hope says. “You start to see not just us, but all the competitors that are out there, (enlist) different models where it makes sense to take bigger risks with films of great ambition.”

Part of the reason for his confidence is that the acquisition prices for films are climbing. Two years ago, the biggest sale out of Sundance was $3.5 million for “The Skeleton Twins,’ This year, “The Birth of a Nation” set a new high-water mark with its $17.5 million sale to Fox Searchlight. Not only did Amazon spend $10 million on “Manchester by the Sea,’ but Netflix shelled out $7 million for the Paul Rudd dramedy “The Fundamentals of Caring” and $5 million for streaming rights to the Ellen Page comedy ‘Tallulah,’ The prospect of financial rewards will inspire artists to bring their best work to the big screen, Hope reasons.

“Movies are being priced correctly again,” he says. “These are bold things for people to do – to put their money behind movies … to put their time … to put all those years … Those are things that are part of the value of the movie.”

Despite this rosy outlook, the reality of the economics are potentially hazardous.

No film by “Manchester by the Sea” director Kenneth Lonergan has ever grossed $10 million at the domestic box office, and Amazon ponied up $14 million for the rights to Allen’s next film, despite the fact that his most recent efforts, “Irrational Man” and “Magic in the Moonlight,’ collapsed in theaters.

That said, Amazon’s business is dramatically different than that of a traditional studio, which still needs a film to break even or make a profit through some combination of ticket sales, home entertainment rentals, and purchases. Amazon doesn’t measure success in box office. Price says he thinks in terms of movie slates, and isn’t concerned if a film marches into the black. With Amazon’s $271 billion market cap, losing a few million on a film won’t make a difference.

“I don’t focus on the individual movie making money,” Price says. “It’s the system that creates value as a whole.”

Making sense of how success is quantified is tricky. Amazon Prime doesn’t just offer its members television shows and films to stream. It is first and foremost a cheaper shipping service, guaranteeing two-day delivery for an annual subscription price of roughly $100. Just as movie theaters exist primarily as a vehicle to sell audiences popcorn, Amazon Prime’s reason for being is to get products to its customers faster. Price says there’s data to suggest that the films and shows Prime customers can access are a draw for them to sign up or renew their membership, but he doesn’t offer any specifics about how they correlate. Nor does he break down subscriber levels, although analysts estimate that Prime has roughly 50 million customers in the U.S.

“We have no idea how many of these subscribers are actually watching video,’ says Tim Mulligan, an analyst at Midia Research. “What we do know is, globally, Netflix is winning the battle. They’re in 190 territories worldwide. Amazon is in five. There’s a recognition that [Amazon needs] to up their game or risk being left behind.”

That kind of arms race requires a lot of cash. Netflix will shell out $5 billion in 2016, and while Amazon isn’t disclosing its programming budget, some analysts estimate it will spend more than $3 billion this year spread over its TV, music and film units. That dwarfs what a smaller distributor is able to spend, and figures to escalate as Amazon starts to develop and produce its own projects, instead of buying completed films at festivals. Amazon estimates that by 2017, at least half of the films it releases will be homegrown.

“The scope of the plan really requires that,’ Berney says. “To do 12-plus films a year, and to be able to expand to have a different outlook, different voices, you really have to have development for that kind of output.”

Of course, that carries risk. It means that Amazon is responsible for budget overruns or auteurs run amok. Just ask Paramount’s Evans, who was burned by Francis Ford Coppola’s attempts to recapture the magic of “The Godfather” on “The Cotton Club,’ or Harvey Weinstein, whose Miramax tenure was nearly derailed when costs spiraled on “Gangs of New York” and “Cold Mountain.”

Amazon’s money won’t be spent on perks. Like other Silicon Valley players, it can seem downright frugal. Instead of a gleaming tower or a sprawling studio lot, its film and television operations are housed several freeways removed from Hollywood, across three floors in a utilitarian Santa Monica building with an open office plan.

For his part, Price embraces the parsimony by making a point of flying coach on business trips.

“I walk by a lot of people in business class who are in this business,” he says. “It’s a small example, but philosophically, it’s meaningful. At the end of the day, the money should be spent on the movies and on things that customers care about.”

HOW TO PRODUCE AN INDIE HIT: USE PATIENCE AND NURTURING

June 18, 2002

By Patrick Goldstein

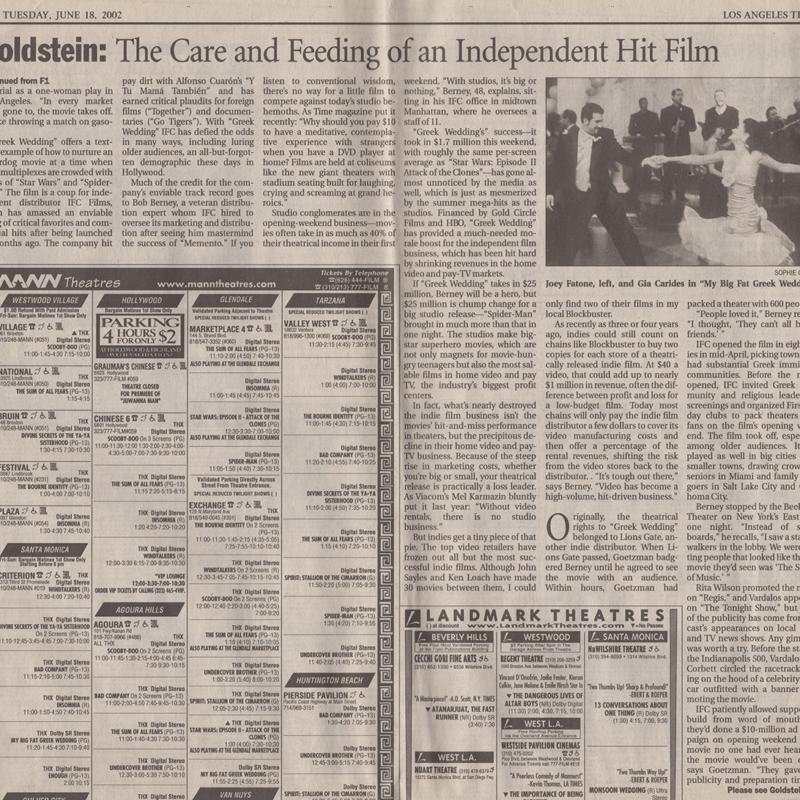

Over the past six weeks, Gary Goetzman has been to 30 cities, going to a different radio station every morning. “I feel like a promotion man working a hit record in the old days of the music business,” says Goetzman, a film producer who got his start in the ’80s in the record industry. Except now, he isn’t touting a hot new single. He’s pitching “My Big Fat Greek Wedding,” the year’s most unlikely hit.

Made for $5 million, spurned by its original distributor and damned with faint praise from critics when it opened in April, the film has been an under-the-radar industry sensation. Now on 455 screens, the movie has taken in $13.6 million so far and is on pace to equal the success of”Memento,” which brought in $25 million two years ago.

Wherever Goetzman goes with the film’s co-stars, Nia Vardalos and John Corbett, there’s an uproar. In Washington, when a female DJ caught sight of Corbett, a regular on HOO’s “Sex and the City,” she flashed her breasts. In Atlanta, the radio station’s secretarial pool emptied out, with everyone lining up to pose for pictures with the stars.

“We don’t have the money to do exit polls, but it’s a pretty good sign when you’re out in a restaurant and you hear people talking about the movie,” says Goetzman, who produced the film with Tom Hanks and his wife, actress Rita Wilson, who initially saw Vardalos do the material as a one-woman play in Los Angeles. “In every market • we’ve gone to, the movie takes off. It’s like throwing a match on gasoline.”

“Greek Wedding” offers a textbook example of how to nurture an underdog movie at a time when most multiplexes are crowded with prints of “Star Wars” and “SpiderMan.” The film is a coup for independent distributor IFC Films, which has amassed an enviable string of critical favorites and commercial hits after being launched 18 months ago. The company hit pay dirt with Alfonso Cuar6n’s “Y Tu Mama Tambien” and has earned critical plaudits for foreign films (“Together”) and documentaries (“Go Tigers”). With “Greek Wedding” IFC has defied the odds in many ways, including luring older audiences, an all-but-forgotten demographic these days in Hollywood.

Much of the credit for the company’s enviable track record goes to Bob Berney, a veteran distribution expert whom IFC hired to oversee its marketing and distribution after seeing him mastermind the success of “Memento.” If you listen to conventional wisdom, there’s no way for a little mm to compete against today’s studio behemoths. As Time magazint• put it recently: “Why should you pay $10 to have a meditative, contemplative experience with strangers when you have a DVD player at home? Films are held at coliseums like the new giant theaters with stadium seating built for laughing, crying and screaming at grand heroics.”

Studio conglomerates are in the opening-weekend business– movies often take in as much as 40% of their theatrical income in their first weekend. “With studios, it’s big or nothing,” Berney, 48, explains, sitting in his IFC office in midtown Manhattan, where he oversees a staff of 11.

“Greek Wedding’s” success-it took in $1.7 million this weekend, with roughly the same per-screen average as “Star Wars: Episode II Attack of the Oones” -has gone almost unnoticed by the media as well, which is just as mesmerized by the summer mega-hits as the studios. Financed by Gold Circle Films and HBO, “Greek Wedding” has provided a much-needed morale boost for the independent film business, which has been hit hard by shrinking revenues in the home video and pay-1V markets.

If “Greek Wedding” takes in $25 million, Berney will be a hero, but $25 million is chump change for a big studio release-“Spider-Man” brought in much more than that in one night. The studios make bigstar superhero movies, which are not only magnets for movie-hungry teenagers but also the most salable films in home video and pay tv, the industry’s biggest profit centers.

In fact, what’s nearly destroyed the indie film business isn’t the movies’ hit-and-miss performance in theaters, but the precipitous decline in their home video and pay- 1V business. Because of the steep rise in marketing costs, whether you’re big or small, your theatrical release is practically a loss leader. As Viacom’s Mel Karmazin bluntly put it last year: “Without video rentals, there is no studio business.”

But indies get a tiny piece of that pie. The top video retailers have frozen out all but the most successful indie films. Although John Sayles and Ken Loach have made 30 movies between them, I could only find two of their films in my local Blockbuster.

As recently as three or four years ago, indies could still count on chains like Blockbuster to buy two copies for each store of a theatrically released indie film. At $40 a video, that could add up to nearly $1 million in revenue, often the difference between profit and loss for a low-budget film. Today most chains will only pay the indie film distributor a few dollars to cover its video manufacturing costs and then offer a percentage of the rental revenues, shifting the risk from the video stores back to the distributor .. “It’s tough out there,” says Berney. “Video has become a high-volume, hit-driven business.”

Originally, the theatrical rights to “Greek Wedding” belonged to Lions Gate, another indie distributor. When Lions Gate passed, Goetzman badgered Berney until he agreed to see the movie with an audience. Within hours, Goetzman had packed a theater with 600 people.

“People loved it,” Berney recalls. “I thought, ‘They can’t all be his friends.'”

IFC opened the film in eight cities in mid-April, picking towns that had substantial Greek immigrant communities. Before the movie opened, IFC invited Greek community and religious leaders to screenings and organized First Friday clubs to pack theaters with fans on the film’s opening weekend. The film took off, especially among older audiences. It has played as well in big cities as in smaller towns, drawing crowds of seniors in Miami and family filmgoers in Salt Lake City and Oklahoma City.

Berney stopped by the Beekman Theater on New York’s East Side one night. “Instead of skateboards,” he recalls, “I saw a stack of walkers in the lobby. We were getting people that looked like the last movie they’d seen was ‘The Sound of Music.'”

Rita Wilson promoted the movie on “Regis,” and Vardalos appeared on “The Tonight Show,” but most of the publicity has come from the cast’s appearances on local radio and TV news shows. Any gimmick was worth a try. Before the start of the Indianapolis 500, Vardalos and Corbett circled the racetrack, riding on the hood of a celebrity pace car outfitted with a banner promoting the movie.

IFC patiently allowed support to build from word of mouth. “If they’d done a $I0-million ad campaign on opening weekend for a movie no one had ever heard of, the movie would’ve been over,” says Goetzman. “They gave the publicity and preparation time to pay off.” IFC ran a similar grassroots campaign with “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” putting up posters in East L.A. restaurants and plastering Latino neighborhoods with billboards adorned with a blurb from actress Salma Hayek. So far the film has grossed $12.3 million.

“The Latino audience is hugely under-served,” says Berney. “They spend a lot of money on entertainment, and if you market something to them, they really respond.” Despite its recent success, IFC still faces a host of challenges. The company has deeper pockets than most independents-its parent company, Rainbow Holdings, owns the Bravo and IFC cable TV channels. Berney hopes these corporate connections can provide some promotional advantages, either by airing making-of documentaries or allowing tie-ins on Bravo’s “Inside the Actors Studio” show.

But having worked at more than one company that overextended itself and went out of business, Berney is cautious; he tries to minimize his risks and milk his successes. He recently persuaded Cuaron to make available both an R-rated and an unrated version of “Y Tu Mama Tambien” so more video stores would stock the film.

“Success puts you on the map,” Berney says. “Instead of us saying, this is what we’re trying to do, we can say we’ve actually done it.” But you can see from the look on his face that Berney knows he’ll have to keep the hits coming to make it as a little guy in a big guy’s business.

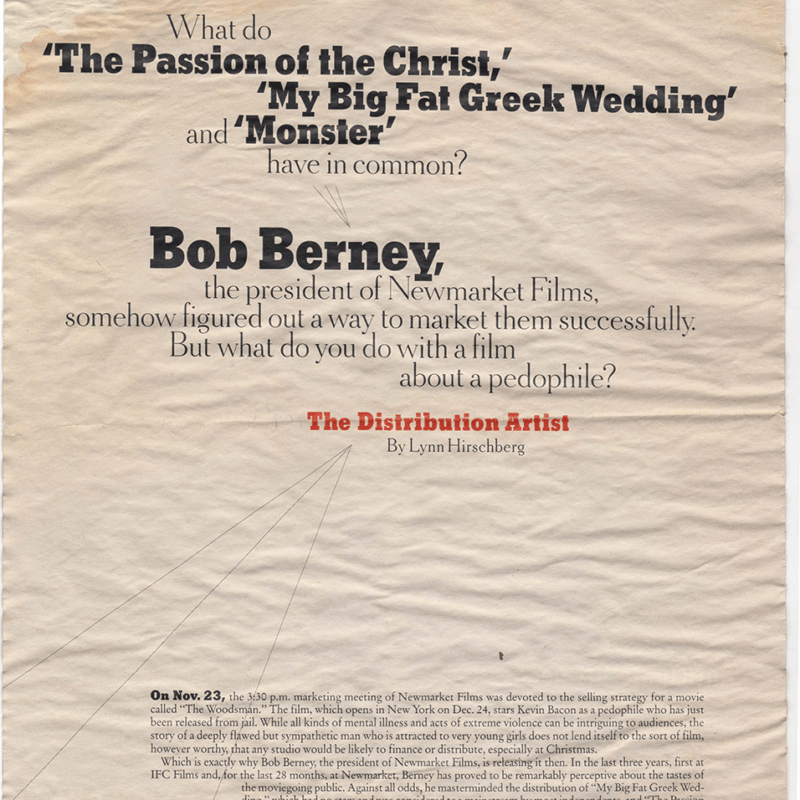

THE DISTRIBUTION ARTIST

December 19, 2004

By Lynn Hirschberg

On Nov. 23, the 3.30 p.m. marketing meeting of Newmarket Films was devoted to the selling strategy for a movie called “The Woods n.” The film, which opens in New York on Dec. 24, stars Kevin Bacon as a pedophile who has just been released from ·ail. While all kinds of mental illness and acts of extreme violence can be intriguing to audiences, the story of a deeply flawed but sympathetic man who is attracted to very young girls does not lend itself to the sort of film, however worthy, at any studio would be likely to finance or distribute, especially at Christmas.

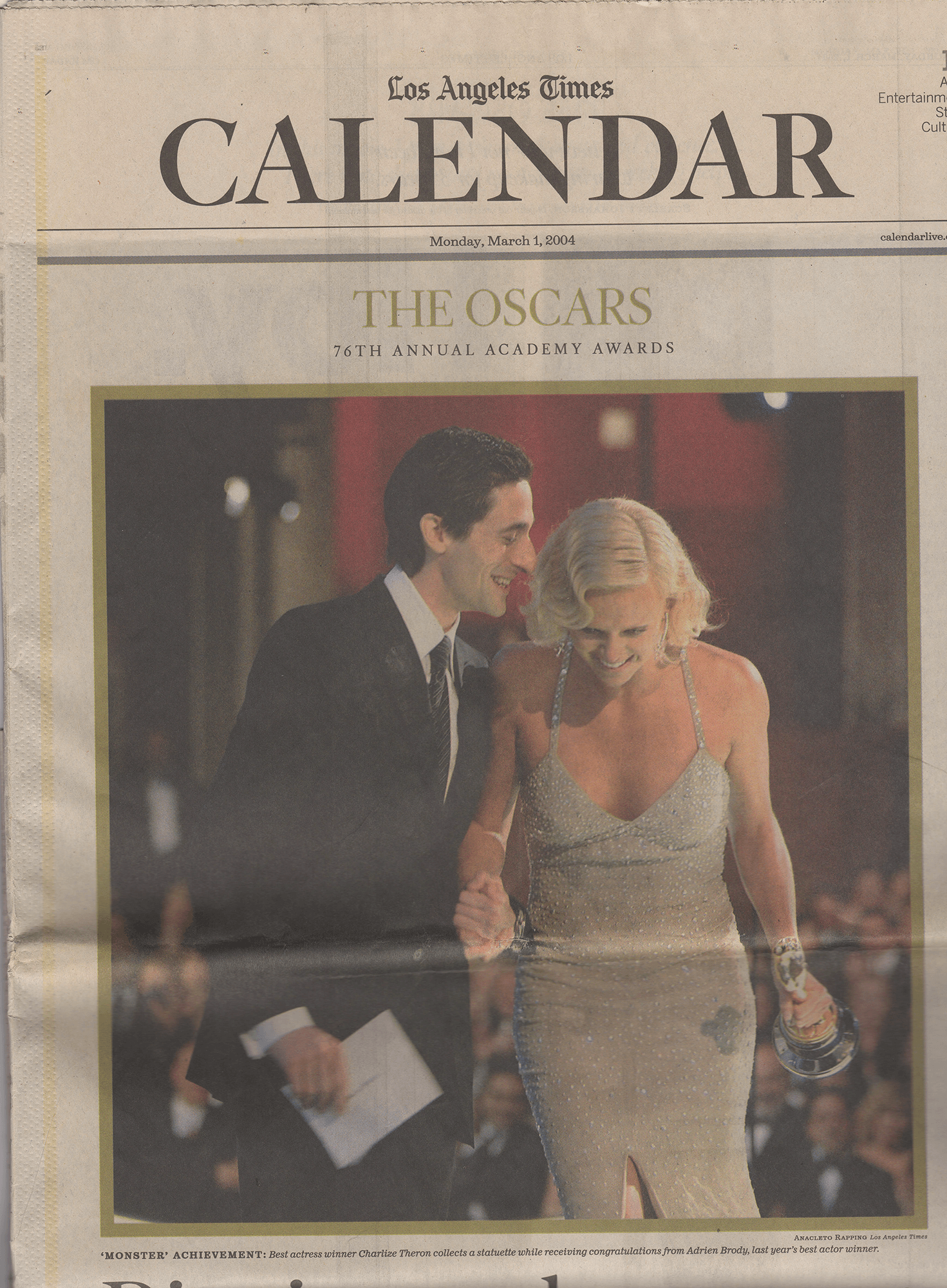

Which is exactly why Bob Berney, the president of Newmarket Films, is releasing it then. In the last three years, first at IFC Films and, or the last 28 months, at Newmarket, Berney has proved to be remarkably perceptive about the tastes of the moviegoing public. Against all odds, he masterminded the distribution of “My Big Fat Greek Wedding,” which had no stars and was considered too mainstream by most independents, and “The Passion of the Christ,” which was rejected by many studios. Those films have earned, respectively, $241.4 million and $370.3 million in the United States, making them by a large margin the two most successful independent films of all time. In 2003, Newmarket released “Monster,” starring Charlize Theron, who gained 30 pounds and wore heavy makeup to play the murderer Aileen Wuornos. “We opened our serial killer, lesbian-prostitute film on Christmas Eve in Manhattan,” Berney said, linking “Monster” to “The Woodsman.” “And it worked.” Theron won practically every award invented, including an Oscar, and the movie, which cost roughly $8 million, went on to make $34.5 million. Newmarket Films and its “genius” (as Theron called Berney) were suddenly the biggest success story in the movie business.

But “Monster” falls into a safer, more familiar cinematic genre than “The Woodsman.” There are protagonists and subject matters that are dark and complex in an interesting way, but pedophilia is too unsettling for most audiences. “Controversy can help a film,” Berney said before the marketing meeting began_”. But I do think this is the one subject that has to be explained. Controversy only works when the controversy is not uncomfortable for people. Pedophilia is not an easily discussed subject.”

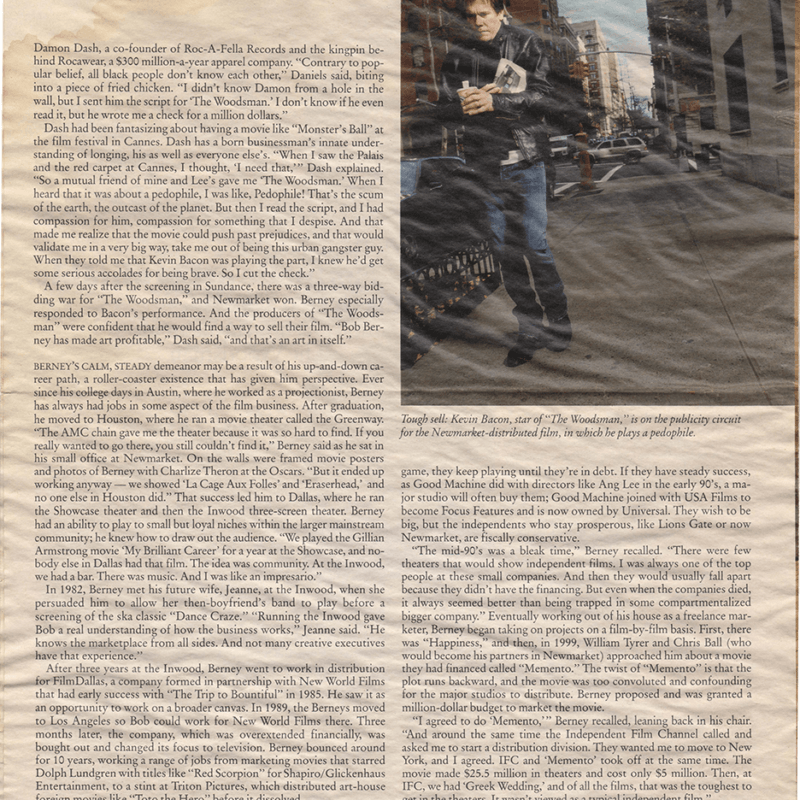

Berney sat down at Newmarket’s modern conference table in a windowless room in the company’s offices near Rockefeller Center. He is an unusually calm man (“It takes me a long time to get angry,” he said, “and, by then, it’s usually too late”) with a soft voice that has a slight drawl, left over from his childhood in Oklahoma. He is a careful dresser and was wearing a white button-down shirt with a subtly woven pinstripe and navy pants. Although he is 51, he has an ageless face that is hard to read. He’s a little opaque, a little blank, which is particularly unusual in the realm of movie moguldom. There is no bombast with Berney, no razzle-dazzle. His effectiveness, unlike Harvey Weinstein’s at Miramax, is not tied to personal showmanship. And yet when Berney talks about “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” the Mexican road movie that he released unrated, or “Whale Rider,” the New Zealand film that nearly every distributor passed on and he made a success, his eyes take on a certain gleeful ferocity. “Bob is kind of an enigma,” Kevin Bacon said, “but I think that’s part of why he’s effective. I wouldn’t want to play poker with him. He’s easy to underestimate and very hard to read. Those traits usually mean you win.”

The extraordinary success of Berney and Newmarket Films (which is owned by Berney and two British financiers, William Tyrer and Chris Ball, who live in Los Angeles) has not gone unnoticed by the studios. This fall, Tom Freston, co-president of Viacom, which owns Paramount, approached Newmarket about purchasing it. The arrangement would be similar to the original deal between Miramax and Disney. Before that relationship soured, Miramax was the autonomous independent wing of the Disney studios, releasing films like “Pulp Fiction” that were quirkier and more daring than its parent studio’s choices. “In the past few years, independent films have become big business,” says Sherry Lansing, the outgoing chairwoman of Paramount. “They are not just quality films that you stick in your release schedule like filler. And Tom Freston wants to release movies he wants to see. Most of the time, those films would come from the ranks of the independents, like Newmarket.”

The movie business is divided into two general parts: production (the coordination and financing of the creative aspect of filmmaking) and distribution (the coordination and financing involved in getting the film to your neighborhood theater). Unlike movies created by the major studios, socalled independent films generally do not have their ov.rn distribution. Small companies like ewmarket, which has 25 employees, are in the business of seeking out finished movies, usually at film festivals, acquiring them and figuring out a way to market them. As an independent distributor, Berney will plan a strategy for a movie’s release. He will often pay for the prints of the film, pick which theaters · will showcase it and create a marketing campaign. With “The Woodsman,” this means promoting Kevin Bacon’s courageous acting and playing down the subject of the movie. It’s tricky: the word “pedophile” does not appear anywhere in the 38- page press kit, and the poster is a photo of Bacon looking down at a little red ball.

“Bob, I just got off the phone,” said Bill Thompson, Newmarket’s head of sales, as he sat down at the conference table for the meeting, “One theater owner who has agreed to show ‘The Woodsman’ was upset about the headline in the London paper that read ‘Pedophile Film Wins Award.’ ‘Pedophile’ was right in the headline. That’s how they described the movie.”

Berney stared a second, but his face remained expressionless. “The Woodsman,” which was directed by Nicole Kassell, had won the Special Jury Prize at the Deauville Film Festival, and the headline was not something he expected. “Well, the theater owners know what the film is,” he said. “They’ve seen it. The hard part is selling it to the public. We want to get the audiences in there to see an important, well-respected Kevin Bacon film in which he happens to play a sex offender out on probation.

Somehow, that sounds better than ‘pedophile.'”

Berney paused. He is aware that the few movies that deal with pedophilia have not done well at the box office. “L.I.E.,” which featured a bravura performance by Brian Cox, lasted just a short time, and in 1998, “Happiness,” directed by Todd Solon dz, was dropped by its initial distributor, Universal, because of its subject matter. Before he arrived at Newmarket, Berney took over the release of “Happiness,” figuring out a way to sell the film from his house in Los Angeles, where he then lived. “I think Bob saved the movie,” Solondz says. “He changed the marketing emphasis from sex to the problems of family life. Bob didn’t want to change the film – he tried to rework the system to fit the movie. Bob is smart, he’s tireless, he’s inventive and he’s also such a pleasant personality, seemingly not saddled with all the neuroses that make ]if e in the movie business long and burdensome.”

“Happiness” went on to make a respectable 53.2 million. “But that movie was different,” Berney said now. “‘The Woodsman’ is not provocative in the same way. This movie, to me, is about the drama of being discovered. That’s what audiences respond to. Everyone has secrets, everyone has shame.”

By now, seven members of the Newmarket staff had gathered around the conference table. Berney has complete faith in the film’s worth, and his quiet, steady belief was contagious. “I guess it sounds arrogant,” Berney had said, “but I am surprised when audiences don’t see what I see in the movies. With ‘Passion of the Christ,’ people were doubtful. We released it on Feb. 25, Ash Wednesday. We put together a plan, which was to go to 2,000 screens right away. That was the riskiest move we ever made as a company. The concern was that the movie might turn out to have a limited appeal and no one would go. If that had happened, we’d be out of money. But Mel” – Mel Gibson, who produced and directed the film – “had always wanted to release it that way, and he liked our plan.”

Berney paused again. He looked down at a mock-up of an ad for “The Woodsman.” He updates and changes the ads for his movies constantly – the first “Woodsman” ad in Variety didn’t even state the title of the film. “More mystery is always good,” he said.

“The Passion of the Christ,” like many of Berney’s films, was helped by positiYe word of mouth and a certain notoriety. Since he has never relied on blanket TV advertising, Berney supports his films through alternative methods, like film festivals, special screenings, radio promotions and Internet marketing. As with “Monster,” most of the campaign for “The Wood man” revolves around its star. “Following Bob’s plan, I’m doing something connected to this movie every day for three straight months,” Kevin Bacon would later tell me. “And that’s until release. Who knows what Bob has in store for me if we get nominations for the Golden Globes or Academy Awards?”

“Let’s see the trailer,” Berney said, as the meeting wound down. Mary Ann Hult, Newmarket’s director of publicity, turned on the TY, which sat next to a ha-If-eaten gift basket of cheese and crackers. The coming-attraction spot was, true to Berney’s vision, all about Bacon’s character having a secret. He has been in jail for something terrible, but he doesn’t say what. He’s talking about his past in a cloudy manner. He’s withdrawn and troubled and finally, compelling. The last line of the trailer – ”I’m not a monster” – is chilling and provocative.

“It’s good,” Berney said. He asked to see another version of the same spot. “I would see that movie,” he said quietly to himself.

There’s a sense of romance in the way that Bob Berney talks about seeing his movies for the first time. He usually encounters them at a screening at a festival with other potential distributors. “I’m always looking for something I can’t predict,” Berney said, over fish and chips at an Irish restaurant around the corner from his office. “It’s a little like falling in love – you couldn’t imagine how this film hadn’t existed in your life before, and then, it’s there.”

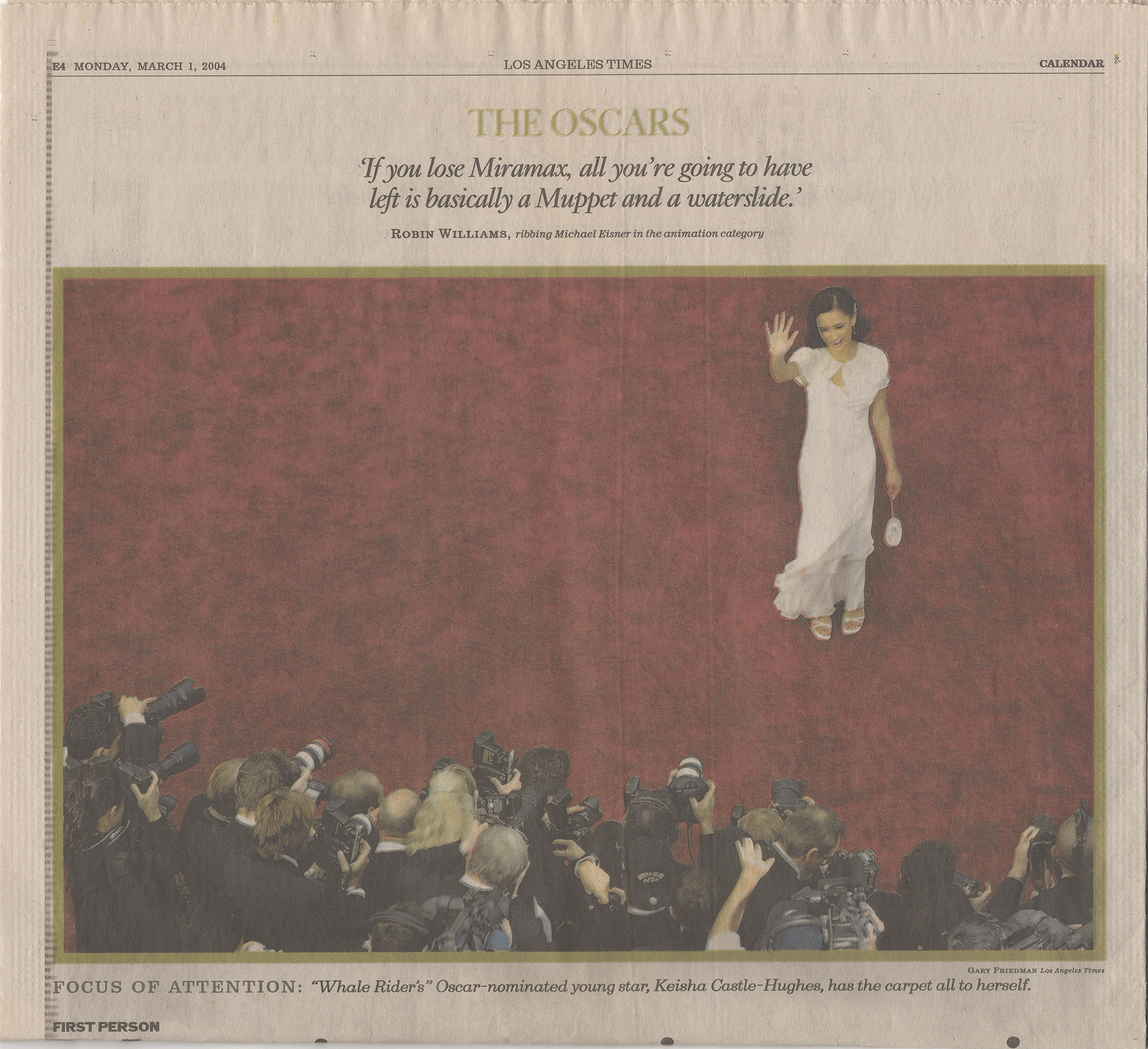

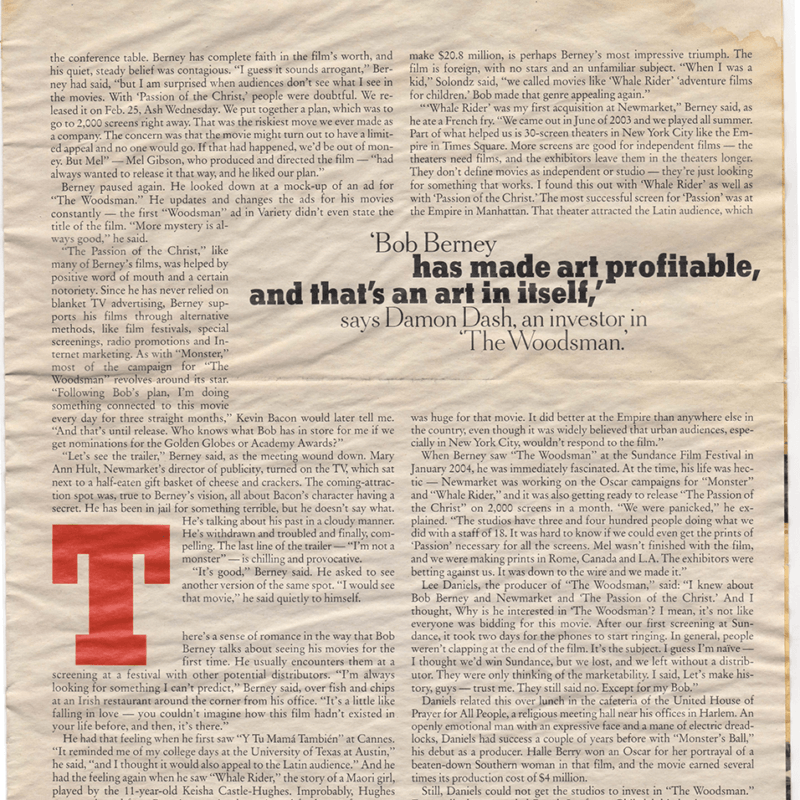

He had that feeling when he first saw “Y Tu Mama Tambien” at Cannes. “It reminded me of my college days at the University of Texas at Austin,” he said, “and I thought it would also appeal to the Latin audience.” And he had the feeling again when he saw ”Whale Rider,” the story of a Maori girl, played by the 11-year-old Keisha Castle-Hughes. Improbably, Hughes was nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award for her performance. The success of “Whale Rider,” which cost $4.5 million and went on to make $20.8 million, is perhaps Berney’s most impressive triumph. The film is foreign, with no stars and an unfamiliar subject. “When I was a kid,” Solondz said, “we called movies like ‘Whale Rider’ ‘adventure films for children.’ Bob made that genre appealing again.”

“‘Whale Rider’ was my first acquisition at Newmarket,” Berney said, as he ate a French fry. “We came out in June of 2003 and we played all summer. Part of what helped us is 30-screen theaters in New York City like the Empire in Times Square. More screens are good for independent films – the theaters need films, and the exhibitors leave them in the theaters longer. They don’t define movies as independent or studio – they’re just looking for something that works. I found this out with ‘Whale Rider’ as well as with ‘Passion of the Christ.’ The most successful screen for ‘Passion’ was at the Empire in Manhattan. That theater attracted the Latin audience, which was huge for that movie. It did better at the Empire than anywhere else in the country, even though it was widely believed that urban audiences, especially in New York City, wouldn’t respond to the film.”

When Berney saw “The Woodsman” at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2004, he was immediately fascinated. At the time, his life was hectic – Newmarket was working on the Oscar campaigns for “Monster” and “Whale Rider,” and it was also getting ready to release “The Passion of the Christ” on 2,000 screens in a month. “We were panicked,” he explained. “The studios have three and four hundred people doing what we did with a staff of 18. It was hard to know if we could even get the prints of ‘Passion’ necessary for all the screens. Mel wasn’t finished with the film, and we were making prints in Rome, Canada and L.A. The exhibitors were betting against us. It was down to the wire and we made it.”

Lee Daniels, the producer of “The Woodsman,” said: “I knew about Bob Berney and Newmarket and ‘The Passion of the Christ.’ And I thought, Why is he interested in ‘The Woodsman’? I mean, it’s not like everyone was bidding for this movie. After our first screening at Sundance, it took two days for the phones to start ringing. In general, people weren’t clapping at the end of the film. It’s the subject. I guess I’m naiveI thought we’d win Sundance, but we lost, and we left without a distributor. They were only thinking of the marketability. I said, Let’s make history, guys – trust me. They still said no. Except for my Bob.”

Daniels related this over lunch in the cafeteria of the United House of Prayer for All People, a religious meeting hall near his offices in Harlem. An openly emotional man with an expressive face and a mane of electric dreadlocks, Daniels had success a couple of years before with “Monster’s Ball,” his debut as a producer. Halle Berry won an Oscar for her portrayal of a beaten-down Southern woman in that film, and the movie earned several times its production cost of $4 million.

Still, Daniels could not get the studios to invest in “The Woodsman.” Eventually, he persuaded Brook Lenfest, a Philadelphia businessman, to invest $1 million, and when he was in Cannes for “Monster’s Ball,” he met Damon Dash, a co-founder of Roe-A-Fella Records and the kingpin behind Rocawear, a $300 million-a-year apparel company. “Contrary to popular belief, all black people don’t know each other,” Daniels said, biting into a piece of fried chicken. “I didn’t know Damon from a hole in the wall, but I sent him the script for ‘The Woodsman.’ I don’t know if he even read it, but he wrote me a check for a million dollars.”

Dash had been fantasizing about having a movie like “Monster’s Ball” at the film festival in Cannes. Dash has a born businessman’s innate understanding of longing, his as well as everyone else’s. “When I saw the Palais and the red carpet at Cannes, I thought, ‘I need that,”‘ Dash explained. “So a mutual friend of mine and Lee’s gave me ‘The Woodsman.’ When I heard that it was about a pedophile, I was like, Pedophile! That’s the scum of the earth, the outcast of the planet. But then I read the script, and I had compassion for him, compassion for something that I despise. And that made me realize that the movie could push past prejudices, and that would validate me in a very big way, take me out of being this urban gangster guy. When they told me that Kevin Bacon was playing the part, I knew he’d get some serious accolades for being brave. So I cut the check.”

A few days after the screening in Sundance, there was a three-way bidding war for “The Woodsman,” and Newmarket won. Berney especially responded to Bacon’s performance. And the producers of “The Woodsman” were confident that he would find a way to sell their film. “Bob Berney has made art profitable,” Dash said, “and that’s an art in itself.”

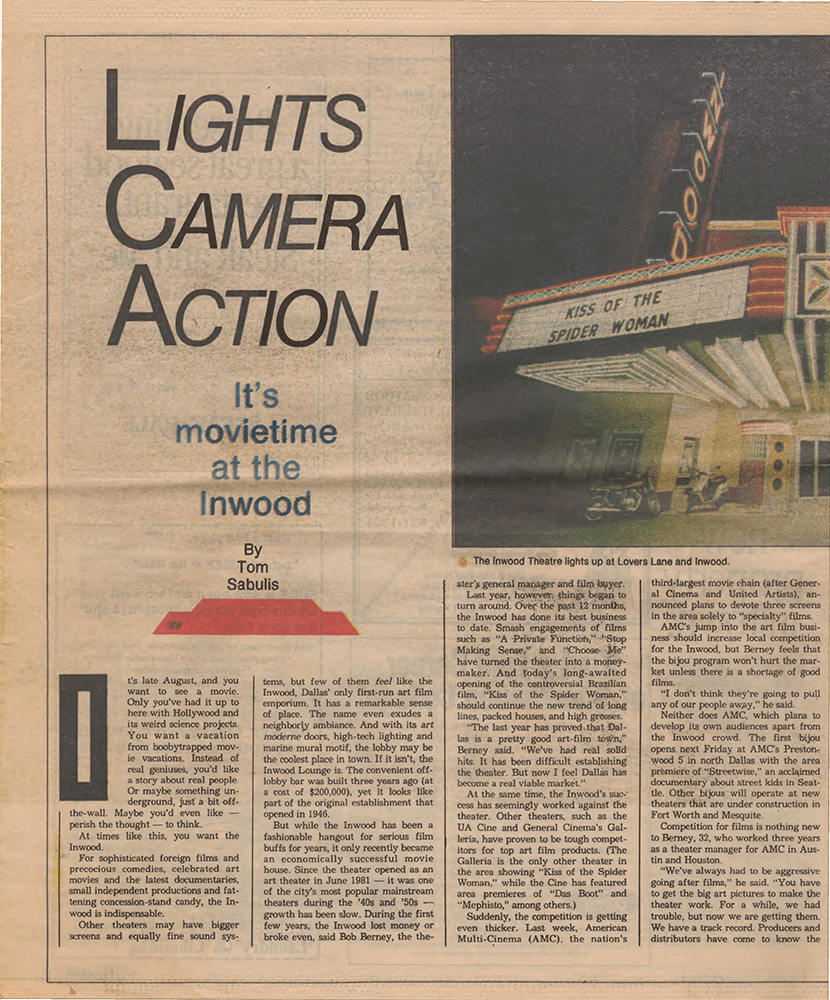

BERNEY’S CALM, STEADY demeanor may be a result of his up-and-down career path, a roller-coaster existence that has given him perspective. Ever since his college days in Austin, where he worked as a projectionist, Berney has always had jobs in some aspect of the film business. After graduation, he moved to Houston, where he ran a movie theater called the Greenway. “The AMC chain gave me the theater because it was so hard to find. If you really wanted to go there, you still couldn’t find it,” Berney said as he sat in his small office at Newmarket. On the walls were framed movie posters and photos of Berney with Charlize Theron at the Oscars. “But it ended up working anyway- we showed ‘La Cage Aux Foiles’ and ‘Eraserhead,’ and no one else in Houston did.” That success led him to Dallas, where he ran the Showcase theater and then the Inwood three-screen theater. Berney had an ability to play to small but loyal niches within the larger mainstream community; he knew how to draw out the audience. “We played the Gillian Armstrong movie ‘My Brilliant Career’ for a year at the Showcase, and nobody else in Dallas had that film. The idea was community. At the Inwood, we had a bar. There was music. And I was like an impresario.”

In 1982, Berney met his future wife, Jeanne, at the Inwood, when she persuaded him to allow her then-boyfriend’s band to play before a screening of the ska classic “Dance Craze.” “Running the Inwood gave Bob a real understanding of how the business works,” Jeanne said. “He knows the marketplace from all sides. And not many creative executives have that experience.”

After three years at the Inwood, Berney went to work in distribution for FilmDallas, a company formed in partnership with New World Films that had early success with “The Trip to Bountiful” in 1985. He saw it as an opportunity to work on a broader canvas. In 1989, the Berneys moved to Los Angeles so Bob could work for New World Films there. Three months later, the company, which was overextended financially, was bought out and changed its focus to television. Berney bounced around for 10 years, working a range of jobs from marketing movies that starred Dolph Lundgren with titles like “Red Scorpion” for Shapiro/Glickenhaus Entertainment, to a stint at Triton Pictures, which distributed art-house foreign movies like “Toto the Hero” before it dissolved.

There were other jobs, too, at other companies that no longer exist. Independent film entities are known for their boom-and-bust sagas. Often, a hit or two makes them flush and then, like a gambler who can’t leave the as Good Machine did with directors like Ang Lee in the early 90’s, a major studio will often buy them; Good Machine joined with USA Films to become Focus Features and is now owned by Universal. They wish to be big, but the independents who stay prosperous, like Lions Gate or now Newmarket, are fiscally conservative.

“The mid-90’s was a bleak time,” Berney recalled. “There were few theaters that would show independent films. I was always one of the top people at these small companies. And then they would usually fall apart because they didn’t have the financing. But even when the companies died, it always seemed better than being trapped in some compartmentalized bigger company.” Eventually working out of his house as a freelance marketer, Berney began taking on projects on a film-by-film basis. First, there was “Happiness,” and then, in 1999, William Tyrer and Chris Ball (who would become his partners in Newmarket) approached him about a movie they had financed called “Memento.” The twist of “Memento” is that the plot runs backward, and the movie was too convoluted and confounding for the major studios to distribute. Berney proposed and was granted a million-dollar budget to market the movie.

“I agreed to do ‘Memento,”‘ Berney recalled, leaning back in his chair. “And around the same time the Independent Film Channel called and asked me to start a distribution division. They wanted me to move to New York, and I agreed. IFC and ‘Memento’ took off at the same time. The movie made $25.5 million in theaters and cost only $5 million. Then, at IFC, we had ‘Greek Wedding,’ and of all the films, that was the toughest to get in the theaters. It wasn’t viewed as a typical independent film.”

As usual, Berney tailored his distribution approach to the film. He suspected “Greek Wedding” would not prosper in a wide release. “We kept it small,” he said. “The tendency would be to go as big as possible, and I didn’t want to do that.” The strategy worked: a film that might have seemed common instead felt special. Berney also enlisted the help of Jeanne, an experienced movie publicist who has worked on many of his movies.

In the summer of 2002, after his rapid success with “Y Tu Mama Tambien” and “Greek Wedding,” Berney abruptly left IFC. “It was a scandal,” Berney admitted. “But Newmarket presented a great opportunity.” He had finally found a company that would not combust.

As film financiers, Berney’s partners at Newmarket had a relationship with Icon, Mel Gibson’s production company. They invested in Gibson’s version of “Hamlet.” When 20th Century Fox, which had rights on the film, decided not to distribute “The Passion of the Christ” in theaters (they found it too controversial), Newmarket was a top contender. Gibson may have also liked that Berney was a practicing Catholic and that his two sons (Sean and Liam, now 15 and 12) had gone to St. Paul the Apostle, a Catholic school in West Los Angeles. “I never told Mel that I was religious,” Berney said. “But they’re like the C.I.A. over at Icon – they just know everything.”

Unlike most independents, Newmarket has always been careful in its business deals. It has missed opportunities in the interest of caution. It could have invested in the production of ”Monster” in its early stages but declined to do so, thereby forfeiting a larger share of the movie’s eventual profits. And on “Passion,” Newmarket’s distribution fee is under 12 percent. Had the company offered to pay for the prints of the film or shoulder the cost of advertising, it could have negotiated a much greater return on its investment. “The Passion of the Christ” may have catapulted Newmarket, but it did not make the company super rich, which is, all things considered, O.K. with Berney. He has seen indies soar and crash, and he’d rather be careful than lose everything.

Newmarket is concentrating on consistency. While it has had some flops – “Stander,” an intriguing movie about a South African cop turned bank robber, lasted only one week last summer in New York – it is not aiming for a high-volume, shoot-the-moon existence. If Newmarket is bought by Paramount in the coming months, it will most likely become Paramount’s answer to Fox Searchlight Pictures. Currently the most consistently interesting specialty division of a studio, Fox Searchlight has excelled at acquisitions (“Napoleon Dynamite”) and production (“Sideways”).

“It all comes down to what choices you make,” Berney said. “I know every movie-theater owner in the country. I like that world, and I spend a lot of time talking to them. They spend a lot of their time trying to figure out the audience. And they all want good movies.” Berney smiled halfway. His desk was covered with “Woodsman” stuff – ads and reviews and a copy of the poster with the strange glowing orb. “You can’t give up on the audience,” he said. “You have to believe they want to see something interesting.”

On a cold, clear night in early December, Bob and Jeanne Berney made their way into the IFP Gotham Awards, New York’s annual celebration of independent films, at Chelsea Piers. They eschewed the red carpet and headed straight into the packed cocktail reception. “You’re a god in Texas,” screamed Jack Foley, the president of distribution at Focus Features. Like nearly everyone here, Foley has known the Berneys “forever” and embraced Bob in a bear hug. “He knew me at the Inwood,” Berney explained. Because Jeanne has worked as a publicist, she greeted almost as many guests as her husband. The couple were like pinballs, bumping into one old friend or business associate ( or both) after another.

Although he clearly enjoyed the social whirl, Berney said the main point of the evening was to generate attention for “The Woodsman.” The day before, the IFP Independent Spirit Award nominations were announced, and “The Woodsman” garnered three, including best male lead for Bacon. But the National Board of Review had not named the film as one of its Top 10. “Awards and mentions are important,” Berney said between hugs. “But most of all, it’s important to generate conversation.”

Tonight, “The Woodsman” was up for two awards – Breakthrough Actor and Breakthrough Director. Bacon and his wife, the actress Kyra Sedgwick (who plays his love interest in “The Woodsman”), were each presenting an award, and Newmarket and Lee Daniels had both bought tables. After an hour of cocktails, the crowd slowly moved into the dining room. The “Woodsman” tables were next to the “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” table, and Jim Carrey posed for snapshots.

Soon, Daniels arrived, and then Damon Dash and the actor and rapper Mos Def, who was nominated for his subtle performance in “The Woodsman.” “Everybody is asking me for money,” Dash said. He had, of course, walked the red carpet. He was, as he often is, followed around by his own camera crew. ‘Tm not really making a movie,” he explained. “It’s more like a reality show.” When he visited the set of “The Woodsman,” Dash arrived by helicopter, as always with entourage and film crew in tow, for the most wrenching scene in the film, in which Bacon’s character relapses and tries to seduce an 11-year-old girl.

Hours later, Daniels was disappointed – “The Woodsman” lost to HBO Films’ “Maria Full of Grace” in both categories. “How could we lose?” he roared. “I’ve seen both movies.” Berney remained sanguine. “The important thing,” he repeated, “is exposure. Kyra and Kevin were presenters, the movie was mentioned all night and we were a big presence.” Daniels, who is as grand in his presentation as Berney is modest, stared a second. “You so understand my journey,” Daniels said, finally, as he hugged Berney. He was soothed.

After another attempt to leave (more hugs, another “You’re a god in Texas”), the Berneys found their car and went back to the Soho House hotel. They live in suburban Bronxville now, Jeanne has taken time off to be with their kids and Bob and Newmarket might soon be bought by a big studio; their fortunes have shifted, probably for good. “I’m happy for the success,” Berney said a few days ago in his office, “but I’ve-learned that you have to concentrate on the current film, not revel in your past triumphs.” He paused. “I’ve always preferred coming at things from another angle.”

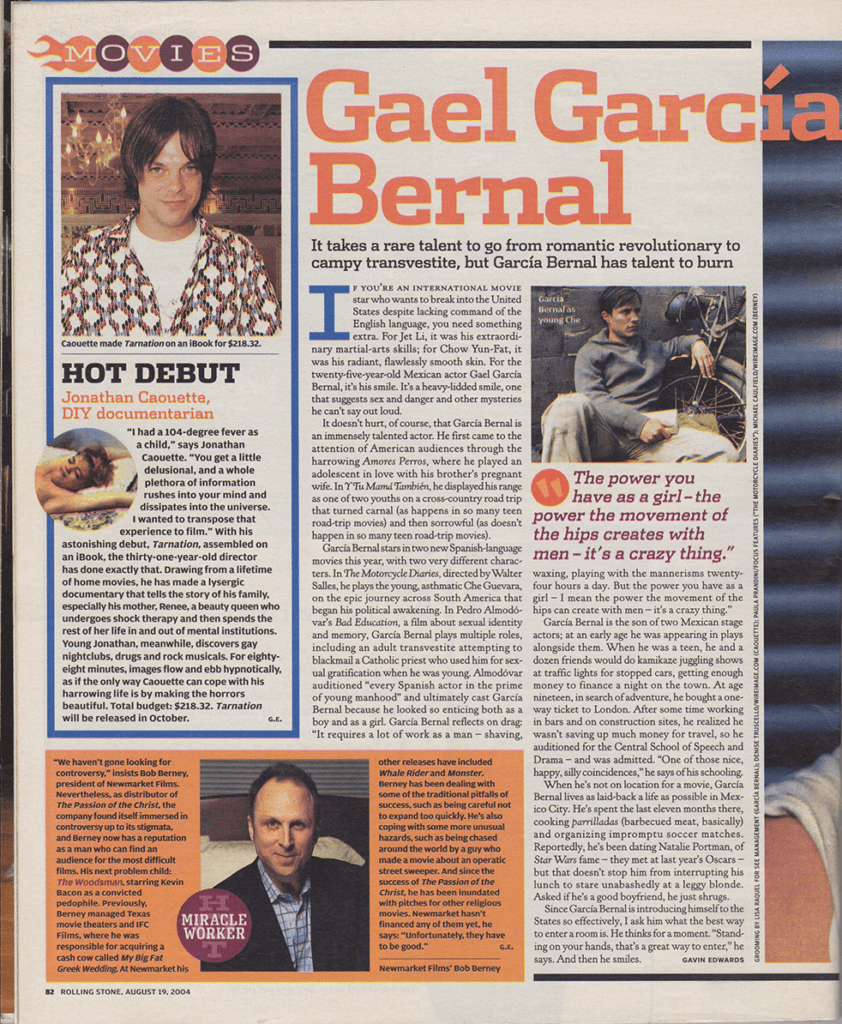

NEWMARKET & CONTROVERSY

August 19, 2004

By Gavin Edwards

HIS WEEK: PASSION AND OSCAR HOPEFULS

By Anne Thompson

Bob Berney is running as fast as he can. The president of the independent distribution company Newmarket Films has beefed up his New York staff to 14 from 8, and he is still hiring. “We’re 24/7,” Mr. Berney said. “We’re lean and mean, we’re at a help-wanted phase.”

Mr. Berney is in the throes of releasing Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” on 4,000 screens on Wednesday – Ash Wednesday. He is also in the final stretch of managing two rival best actress Oscar campaigns, for Charlize Theron (“Monster”) and Keisha Castle-Hughes (“Whale Rider”). His two actresses and their entourages are now back here for the final week before the Oscars, which just happens to be the same week that “The Passion” opens.

Mr. Gibson turned to Newmarket Films to book theaters and to handle television spots, trailers and print ads after he was unable to land a satisfactory studio deal for his selffinanced $30 million drama starring Jim Caviezel as Jesus, which is rated R for its intense violence. (Mr. Gibson’s company, Icon Productions, has had a long investment relationship with Newmark Capital Group, parent company of Newmarket Films.

“Bob carries with him, always, a quiet assurance,” said Mr. Gibson, who is paying Newmarket 10 percent of the distributor’s share of box-office receipts. (Icon keeps the rest.) “You instantly know you’re in the presence of someone very shrewd and effective in achieving his goal.”

Mr. Berney said: “Our job is to make it seem like the story of Jesus done in ‘Braveheart’ style. Mel Gibson is the star. A lot of people don’t know that he isn’t in it.”

Icon is handling the publicity, through Mr. Gibson’s publicist, Alan Neirob, at Rogers & Cowan, and a consultant for religion-based marketing, Paul Lauer. Box-offfce tracking research indicates that the movie could earn $35 million to $50 million in its opening five days, and as much as $150 million in domestic ticket sales.

The number of theaters to show the movie has increased to 3,000 from 2,000, Mr. Berney said. “Theaters are adding two to four screens in each complex, based on demand,” he said. “They have advance sales of $10 million. They’ve been inundated with calls from church groups.” At one Orange County, Calif., theater, Mr. Berney said, “a woman brought $11,000 in cash and bought out as many shows as she could.”

Now Newmarket’s skeleton staff is struggling to cope with the film’s expanding release pattem “Four thousand prints for a studio is no such a big deal.” Mr. Berney said. “But this is an indie release.” (It Took ‘My Big Fat Greek Wedding” six months to reach 1000 screens.) To manufacture 4,000 prints at the last minute, Newmarket had to use labs not only in the United States but also in Canada and Italy.

Mr. Berney is on a winning streak. His rivals say they marvel at his intuitive ability to read the marketplace. “He has a gut instinct for how to roll out a film,” said Sarah Rose, a United Artists acquisitions executive, “when to blink and when to roll the dice and keep going.” Industry colleagues say his wife, Jeanne, who does much of his publicity, and his longtime lieutenant Rob Schwartz, who deals with exhibitors, round out the Berney brain trust.

Mr. Berney’s surprise hits are piling up: the 2001 time-twisting thriller “Memento,” with $25 million in ticket sales, and the sexy Mexican com. edy “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” with $13 million, and in 2002 “My Big Fat Greek Wedding,” which brought in $~41 million, the largest amount ever for an independent film.

With “Greek Wedding” Mr. Berney followed his usual strategy. He built from a core target audience in certain cities, then slowly widened ‘ the release pattern until he made the crucial jump from the art houses to the suburbs, where the real money is.

An Oklahoma native, Mr. Berney studied film at the University of Texas at Austin, managed a Dallas arthouse theater, then worked in independent distribution in Los Angeles. He was consulting on his own in 1998 when he released an unrated film by Todd Solondz, “Happiness.”

“I respond to something that, on the surface is too challenging or off- beat,” Mr. Berney said, “but I can Ted Hope, who produced “Happiness,” said, “Bob demonstrated that you use the art houses as early adopters.”

Newmarket Capital Group officials approached Mr. Berney with their quirky thriller-in-reverse “Memento,” a festival hit that had found no buyers, and Mr. Berney persuaded them to let him release it. They – made a handshake deal. “They just said, ‘You go do it,’ ” Mr. Berney said. “I didn’t have a lot of barriers.” He took the movie to $25 million and a screenwriting Oscar nomination. see a way to sell it.”

He joined IFC Films in New York, . and his run continued with the unrated subtitled comedy “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” which scored with both Hispanic and Anglo audiences, earning $13 million.

After he released “Greek Wedding,” Newmarket, which has financed more than 75 movies in 18 years, lured him away from IFC with an equity offer. “It took me a long time to find the right people who were willing to take the risk on theatrical distribution,” Mr. Berney said. “It takes guts and some understanding of the long term.”

He seems to have found the financial ability and freedom he was seeking. He scooped up the New Zealand coming-of-age drama “Whale Rider” at the 2002 Toronto Film Festival for $1 million, just before it won the People’s Choice Award. Newmarket counterprogrammed the film, about a Maori girl, against the season’s Rrated car-crash movies; it chugged through the summer to $21 million.

Ms. Castle-Hughes was overlooked by the Golden Globes. But “Whale Rider” reached its widest audience during awards season through its DVD release. When the Academy’s actors branch placed the 13-year-old Ms. Castle-Hughes in the best actress category on the Oscar ballots, she became the youngest nominee ever in that category.

When the director Patty Jenkins showed distributors “Monster,” the true story of Aileen Wuornos, a serial killer, “the feedback was that this was an incredibly hard movie to sell,” Ms. Theron, recalled.

“I was willing to work with anybody and do anything to get it,” Mr. Berney said. Newmarket swiftly organized a late December release for “Monster,” complete with an Oscar campaign for the shape-shifting Ms. Theron, who thanked Mr. Berney when she accepted her Golden Globe. After the Jan. 27 Oscar nominations Mr. Berney bumped “Monster” to 800 screens from 300. If Ms. Theron wins an Oscar on Sunday, the movie’s screen count ·could go to 1,300, and this little problem child of a movie could reach $30 million.

Mr. Berney, 50, said he would not pursue a wide release like “The Passion” again any time soon. “There’s a lot of momentum when you’re on a roll,” he said. “It’s like blackjack.” He added that he hoped his luck would now extend to films he picked up at festivals, like “Stander,” a South African thriller starring Thomas Jane ; the Danish black comedy “The Green Butchers”; and the Sundance Film Festival hit “The Woodsman,” starring Kevin Bacon as an improbable hero: a pederast. Next fall watch Mr. Berney try to get Mr. Bacon an Oscar nomination.

A WINNING BET ON AN UNUSUAL MOVIE

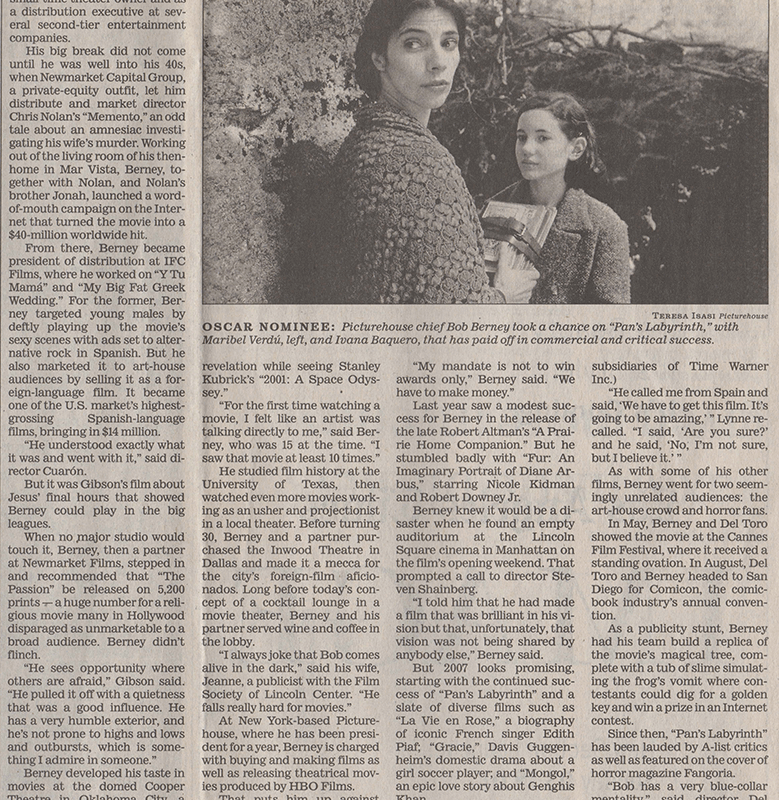

The road to tonight’s Oscars for “Pan’s Labyrinth,” a nominee for best foreign-language film, can be traced to a meal of fried eggs and truffles at a Madrid restaurant.

On a blazing hot August night, between sips of red wine, director Guillermo del Toro asked studio executive Bob Ber-· ney to look at images on a laptop of a giant slime-regurgitating frog and a pale creature-man without eyes.

“As I saw bits and pieces of it, like the frog and everything, it seemed exciting to me,” Berney said.

Berney knew he had found something special for Picturehouse, the movie venture he heads for HBO Films and its sister company New Line Cinema. His hunch proved right: The $18- million film about the imaginary world of a girl in fascist Spain is a commercial and critical hit, on track to gross at least $70 million worldwide and boasting six Academy Award nominations.

It’s those instincts that have made Berney an important figure in the independent film world. He turned such tough sells as “Memento,” “Whale Rider:• and “Y Tu Mama Tambien” into mainstream hits through clever marketing and a knack for getting them into the right theaters. He was crucial in making Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” a blockbuster and helped guide “My Big Fat Greek Wedding” into one of the most profitable independent runs ever.

“He is like your pediatrician,” said director Alfonso CUar6n, who directed “Y Tu Mama Tambien” and produced “Pan’s Labyrinth.” “He sees your movie like a child that you hand over to him. And then he stays with the kid until he becomes a Nobel Prize winner.”

The soft-spoken, unassuming Oklahoman has had an unconventional Hollywood career. Now 53, Berney toiled for years in the guts of the entertainment business – working as an usher, as a small-time theater owner and as a distribution executive at several second-tier entertainment companies.

His big break did not come until he was well into his 40s, when Newmarket Capital Group, a private-equity outfit, let him distribute and market director Chris Nolan’s “Memento,” an odd tale about an amnesiac investigating his wife’s murder. Working out of the living room of his then- • home in Mar Vista, Berney, together with Nolan, and Nolan’s brother Jonah, launched a word of- mouth campaign on the Internet that turned the movie into a $40-million worldwide hit.

From there, Berney became president of distribution at IFC Films, where he worked on “Y Tu Mama” and “My Big Fat Greek Wedding.” For the former, Berney targeted young males by deftly playing up the movie’s sexy scenes with ads set to alternative rock in Spanish. But he also marketed it to art-house audiences by selling it as a foreign- language fIlm. It became one of the U.S. market’s highest grossing Spanish-language films, bringing in $14 million.

“He understood exactly what it was and went with it,” said director Cuaron.

But it was Gibson’s film about Jesus’ final hours that showed Berney could play in the big Leagues.

When no major studio would touch it, Berney, then a partner at Newmarket Films, stepped in and recommended that “The Passion” be released on 5,200 prints – a huge number for a religious movie many in Hollywood disparaged as unmarketable to a broad audience. Berney didn’t flinch.

“He sees opportunity where others are afraid,” Gibson said. “He pulled it off with a quietness that was a good influence. He has a very humble exterior, and he’s not prone to highs and lows and outbursts, which is something I admire in someone.”

Berney developed his taste in movies at the domed Cooper Theatre in Oklahoma City, a high-end movie house that served European chocolates instead of popcorn. Before each film, an American flag the size of the screen was unfurled and the Pledge of Allegiance was recited. It was there that Berney had a revelation while seeing Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

“For the first time watching a movie, I felt like an artist was talking directly to me,” said Berney, who was 15 at the time. “I saw that movie at least 10 times.”

He studied film history at the University of Texas, then watched even more movies working as an usher and projectionist in a local theater. Before turning 30, Berney and a partner purchased the Inwood Theatre in Dallas and made it a mecca for the city’s foreign film aficionados. Long before today’s concept of a cocktail lounge in a movie theater, Berney and his partner served wine and coffee in the lobby.

“I always joke that Bob comes alive in the dark,” said his wife, Jeanne, a publicist with the Film Society of Lincoln Center. “He falls really hard for movies.”

At New York-based Picturehouse, where he has been president for a year, Berney is charged with buying and making fIlms as well as releasing theatrical movies produced by HBO Films. That puts him up against such established operations as 20th Century Fox’s Fox Searchlight and Universal Pictures’ Focus Features, both of which have been successful at finding quality specialized fIlms that have commercial appeal.

“My mandate is not to win awards only,” Berney said. “We have to make money.”

Last year saw a modest success for Berney in the release of the late Robert Altman’s “A Prairie Home Companion.” But he stumbled badly with “Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus,” starring Nicole Kidman and Robert Downey Jr.

Berney knew it would be a disaster when he found an empty auditorium at the Lincoln Square cinema in Manhattan on the fIlm’s opening weekend. That prompted a call to director Steven Shainberg.

“I told him that he had made a film that was brilliant in his vision but that, unfortunately, that vision was not being shared by anybody else,” Berney said.

But 2007 looks promising, starting with the continued success of “Pan’s Labyrinth” and a slate of diverse films such as “La Vie en Rose,” a biography of iconic French singer Edith Piaf; “Gracie,” Davis Guggenheim’s domestic drama about a girl soccer player; and “Mongol,” an epic love story about Genghis Khan.

“Pan’s Labyrinth” has boosted Berney’s reputation for making the right gambles, especially with his bosses, HBO Films President Colin Callender and Michael Lynne, co-president of New Line. (The companies are subsidiaries of Time Warner Inc.)

“He called me from Spain and said, ‘We have to get this film. It’s going to be amazing,’ “Lynne recalled. “I said, ‘Are you sure?’ and he said, ‘No; I’m not sure, but I believe it.”

As with some of his other films, Berney went for two seemingly unrelated audiences: the art-house crowd and horror fans.

In May, Berney and Del Toro showed the movie at the Cannes Film Festival, where it received a standing ovation. In August, Del Toro and Berney headed to San Diego for Comicon, the comicbook industry’s annual convention. As a publicity stunt, Berney had his team build a replica of the movie’s magical tree, complete with a tub of slime simulating the frog’s vomit where contestants could dig for a golden key and win a prize in an Internet contest.

Since then, “Pan’s Labyrinth” has been lauded by A-list critics as well as featured on the cover of horror magazine Fangoria.

“Bob has a very blue-collar mentality,” said director Del Toro. “He rolls up his sleeves and gets to work …. He always had a very clear idea about the movie’s first mission being emotion. With that element, it travels.”

BERNEY GOES TO NEWMARKET

July 24, 2002

By Ian Mohr

TURF WARS, NOT STAR WARS

April 18-24, 2005

By Peter Bart

SCREEN INTERNATIONAL

By Mike Goodrich

On Wednesday, Feb 25, in the early hours of the morning, crowds will start gathering outside the Tinseltown 20 Multiplex in Plano, a middle-class suburb of Dallas, Texas.

It’s Ash Wednesday. The event: the first show of the opening-day screening of Mel Gibson’s THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST. At 6.30am, the 125-minute film will begin playing on not one, not 10, but all 20 of the screens. In fact, at the time of writing (Jan 22), all 20 screens are sold out for all the shows of the film until the evening.

For Newmarket Films, the independent distributor which has partnered with Gibson’s Icon Entertainment on the theatrical release of the picture, the demand for the film is unprecedented and should continue right through Lent to Easter. This kind of demand is unprecedented for most Hollywood studio blockbusters. For all the controversy which has plagued Gibson’s third film as a director, the major – nay, monster – commercial success of the film is now almost a given.

For the majors which turned down the film, the demand for THE PASSIION is a big lesson. The conservative religious population in the US is a potentially massive cinema-going demographic which was underserved by Hollywood until Gibson, an A-list star if ever there was one, decided to make his personal, RomanCatholic film of the passion. Gibson isn’t even in the picture; his stars are Jim Caviezel as Jesus, Romania’s Maia Morgenstern as Mary and Italy’s Monica Bellucci as Mary Magdalene; the film is in the (dead) Aramaic language, is subtitled and contains brutal scenes of violence against Christ which have earned it an ‘R’ rating in the US. But this particular audience doesn’t care that it’s subtitled, violent and doesn’t have stars in it:this isn’t the upscale audience of LosAngeles or New York City, nor teenagers or African Americans or any other key demographic. This is Middle America. Welcome to the Bible Belt.

Bob Berney, the independent distribution veteran who is a partner in Newmarket Films and runs the company’s distribution activities, explains that the combination of Gibson, a supremely bankable star in Middle America, and The Bible is an extraordinary one. “They want to know what Mel Gibson’s take is,” he explains. “Gibson is probably the most popular movie star in the country and he definitely is in the world of Reader’s Digest readers.

“The film, which is only now starting to screen for press, is,” says Berney, “intense. It’s the last 12 hours of Christ’s life, with flashbacks, and is quite an experience. People who have seen it are stunned and can’t talk at the end of it. Mel is trying to humanize the bible story and therefore it’s very violent. We got the R rating from the MPM after some discussion. Some kids will be horrified, but it’s not a family movie. We are working in the campaign to educate families as to this fact in advance, so that, if they take kids, they will take older kids rather than younger.”

Good reviews, says Berney, are not a priority as they would be in the smaller arthouse films which he is such an expert at releasing: “It’s a powerful and moving film and I think it will get good reviews, but only if critics can review the film and not Mel. Some won’t be able to get past it.”

So how has this subtitled, ‘R’-rated, violent picture reached such a fever pitch of excitement in the US? Berney explains that Icon and Newmarket have worked together in the past on financing agreements and that Newmarket’s Will Tyrer approached Gibson’s partner at Icon, Bruce Davey, about handling the domestic release of the film when Icon’s studio partner 20th Century Fox and others passed on it after accusations of anti-semitism started flying at Gibson from Jewish groups, none of which had seen the film.

Icon had already hired a consultant called Paul Lauer to devise a strategy targeting different churches and work on a grassroots religious campaign. “They were trying to build awareness in the churches like you would a political campaign, and while this was going on, we started to realize the scope of the film. Since we took on the film, we have had hundreds of thousands of calls from churches asking how to get advance tickets and free tickets. Most of the exhibitors started asking for two _or three prints per complex. We decided that we should go as wide as possible to begin with.”

And it’s not just the Catholic Church which approved the film – although whether the Pope himself uttered the now-famous edict, “It is as it was,” has been disputed by Vatican sources. Even leaders in the Southern Baptist church which usually condemns Hollywood product and certainly disapproves of ‘R’rated films, has told its congregations that they can go to the film.

Once the film was screened to leaders of various churches and they officially endorsed it, fliers were sent out into the church communities and screenings were set up to drive word of mouth. The official The Passion website started to get millions of hits a day. Meanwhile, the controversy and Gibson’s name have fueled interest in traditional media outlets and want-to-see among non-religious audiences. Gibson’s publicist Alan Nierob, who is based at Rogers & Cowan in Los Angeles, has worked closely with Newmarket to combat the negative publicity on the film. The teaser trailer was premiered on ABC morning show “Good Morning America” and the first trailer was premiered on CBS show “Entertainment Tonight”.

”After that,” says Berney, “the website went through the roof. After the trailers went out on those network shows, we started to get enquiries about group sales. The major circuits like Regal, Cinemark and AMC have set up their own 800 numbers and internet sites to go to for information on tickets.”

Astonishingly, six or seven weeks before Feb 25, most circuits had set the daily times and schedules of the film in its first few weeks, when normally the times are not set in stone until a fortnight before opening.

Gibson himself has personally screened the film for numerous church and religious groups and will continue to do so to further the grassroots campaign, but he won’t spend too much rime on the road tubthumping for publicity purposes. Instead, the star has opted to do select interviews with key press and TV outlets, preferring the spotlight to fall on his actors.

He did, however, attend the Ain’t It Cool News (AICN) Film Festival, which was held recently in Austin, Texas, where he was interviewed on stage after the screening by Harry Knowles, the founder of the maverick website. “If you go to the festival, you have to watch movie after movie for 24 hours,” says Berney, “and THE PASSION was the final film, but the response was incredible from the audience, which was composed of internet geeks and was not religious.”

Even Jewish groups will want to see the film, thinks Berney: “So much has been written about it which was negative without anyone seeing the film. It certainly is very upfront about its Catholic faith, but it’s not anti-semitic, and the Jewish community will want to see it for themselves.”

Opening on some 2,200 sites, THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST is the widest ever opening for a subtitled film and, although Berney won’t be drawn on estimates, it is expected to top $30m in its first weekend and maybe outgross the $128m taken by previous top subtitled film CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON.

The question remains as to whether it will inspire Hollywood studios to look at the sleeping giant that is the Christian audience in a different light. After all, Hollywood never used to shy away from spending tens of millions of dollars to produce religious epics like QUO VADIS?, BEN-HUR, KING OF KINGS, THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD, THE TEN COMMANDMENTS and THE ROBE. Those films are not only classics but some of the biggest moneyspinners in history.

An indication will be where the video rights land for the film, a deal Icon has not yet opted to make. Certainly Fox and the other studios, only a few weeks ago shying away from THE PASSION out of political correctness, will now be looking hungrily at its long-term value on DVD and video, not to mention in non-theatrical arenas and direct mail markets. No longer a hot potato, THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST has quickly evolved into one of the year’s must-see hot tickets.

IT'S MOVIETIME AT THE INWOOD

By Tom Sabulis

Berney’s Roll Call Of Success