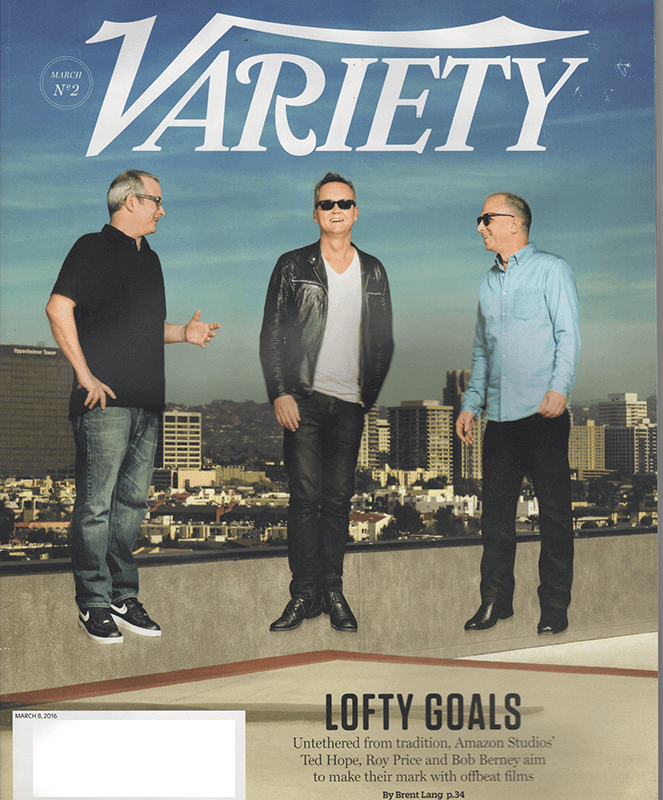

AMAZON STUDIO PLOTS ITS COURSE

March 8, 2016

By Brent Lang

As snow fell steadily, blanketing the mountainside town of Park City, the team from Amazon Studios huddled in a parking lot to discuss the movie that had just premiered at the Sundance Film Festival.

Moments before, the drama ‘Manchester by the Sea,’ a finely calibrated portrait of grief and loss, had received a standing ovation, triggering predictions on social media that the picture would be a major Oscar contender. As the credits rolled, potential buyers rushed to the exits. Amazon Studios chief Roy Price, who was stuck in the middle of a long row of moviegoers, had to vault over seats to get out of the packed theater.

“We were out afterward in the cold, shivering,” recalls Ted Hope, head of motion picture production at the company. “We were all agreeing on the same thing – that we saw something that doesn’t come around much.”

It was a crucial moment for Amazon. After largely sitting out the major festivals and markets, or falling short in its bid to land acclaimed films like ‘Brooklyn,’ the movie arm of the Seattle-based streaming giant needed to make a splash. Just before 2 a.m., the Amazon executives scrunched into a sports utility vehicle to make their way up a Park City mountain, where the “Manchester” creative team and a phalanx of agents were hearing pitches from the likes of Sony, Universal, Fox and Lionsgate.

“The car is swerving,” says Hope. “I’m going out on a mountain ledge to risk my life to buy this film. You can’t even see. They don’t make windshield wipers fast enough to go back and forth for the snow.”

Hours of haggling and $10 million later, Amazon had nabbed its prize. It would leave Sundance with four acquired films, including the quirky comedy “Wiener-Dog”, the acclaimed documentaries “Gleason,” a look at an NFL star battling ALS, and ”Author, The JT Leroy Story,’ an examination of a literary fabulist.

“It’s like the T-1000,’ says Graham Taylor, head of global finance and distribution at WME, the agency that sold Amazon most of its Sundance purchases, referring to the next-gen Terminator. “They’re getting faster, smarter, more operationally nimble.”

Amazon’s buying blitz broadcast the company’s ambitions to carve out a niche as a destination for prestige films at a time when major studios are focused on big-budget spectacles. In the process, Amazon is upending the independent film space. Along with Netflix, which paid top price last year for “Beasts of No Nation,” and recently bid $20 million but failed to land slave drama “The Birth of a Nation,” Amazon is shelling out the kind of money that would be ruinous for a Sony Pictures Classics or A24. The gap between these giants and smaller, pluckier players will only widen as other tech titans such as Apple and Hulu dive into the original content business.

”Amazon has a track record of going into various industries and blowing away the competition,” says Will Richmond, an analyst at VideoNuze.

While the primary source of corporate parent Amazon’s business is e-commerce and shipping, there’s a reason the company has intensified its push into digital video, analysts say. Just as Amazon foresaw that the rise of the Internet would fracture the retail business, new technology is now splintering the entertainment landscape. The ground is shifting under the broadcast and cable industries as audiences move online, and there’s an opportunity for aggressive players to capture this migrating consumer base.

“The state of play in the video industry is very unsettled, and among large companies like Amazon, Google, Apple and Netflix, there’s very much a land-rush mentality,” Richmond says.

But the Amazon model differs from that of Netflix. Whereas Netflix debuts its films on its streaming service, only grudgingly agreeing to screen them in theaters when it needs to qualify for awards, Amazon adheres to a more traditional distribution strategy. It partners with indie distributors, such as Roadside or Bleecker Street, to release movies in theaters, and then makes them available through its Prime subscription service in what is traditionally known as the pay-television window – the time when a film would run on an HBO or Showtime. Every Amazon film will get a theatrical release, but that time period can range from an abbreviated 30 days in cinemas to a standard 90 days.

This model has won the company the loyalty of filmmakers such as Spike Lee, whose ‘Chi-Raq,’ a look at gang violence in Chicago, became Amazon’s first theatrical release last December.

“Maybe I’m old-fashioned, but I like my films to be in a theater first before people watch it on an iPhone,” says Lee.

Months after fleeing the snow drifts of Park City, Price sat in a Midtown Manhattan restaurant, sipping tea while sketching out his ambitious plans to make Amazon a force in movies, just as it is in television. He wants the company to release between 10 and 12 films a year, with budgets ranging from $5 million to $40 million. Price hopes the studio will become the kind of standard bearer for quality that Paramount Pictures was under Robert Evans in the 1970s, a time that saw the release of “The Godfather” and “Chinatown,’ and that Miramax was in its ’90s “Pulp Fiction” heyday.

Whereas Netflix has signed deals with the likes of Adam Sandler and Pee Wee Herman in the hopes of reaching the broadest possible audience, Amazon has moved in a quirkier direction. It’s backing projects from Whit Stillman (“Love & Friendship”), Todd Solondz (“Wiener-Dog”), and an untitled film from Woody Allen – directors who are admired by critics, but have limited commercial appeal.

“‘Mall Cop’ is a very funny film, and someone should make it, but that’s not what we’re doing,” says Price, whose casual look is often carried off with a white T-shirt, black leather jacket and sneakers. “We want to work with visionary film makers who are making interesting films that you’re still going to be talking about in three years,’

That’s how Amazon has made waves on the television side of the business – by rolling the dice on edgy and offbeat original works such as “Transparent,” a comedy about a family dealing with a transgender parent, and ‘Mozart in the Jungle,’ a dramedy set in the world of classical music. They’re the kinds of projects that would struggle to get a pilot order or would be, in the words of “Transparent” creator Jill Soloway, so “bologna-fied” that they would lose their distinctive qualities.

“So often the tone is the first thing to leak out,” Soloway says. “It’s the victim of all the smallish political necessities that go with working with networks. There are all these people involved with every decision, and they’re telling you things need to be brighter, shinier, more about wish fulfillment, and the women need to be prettier.”

At Amazon, Soloway says, the approach is more streamlined, with fewer layers of bureaucracy to navigate. It’s been smart for business. Giving their showrunners more freedom has resulted in Emmys and Golden Globes.

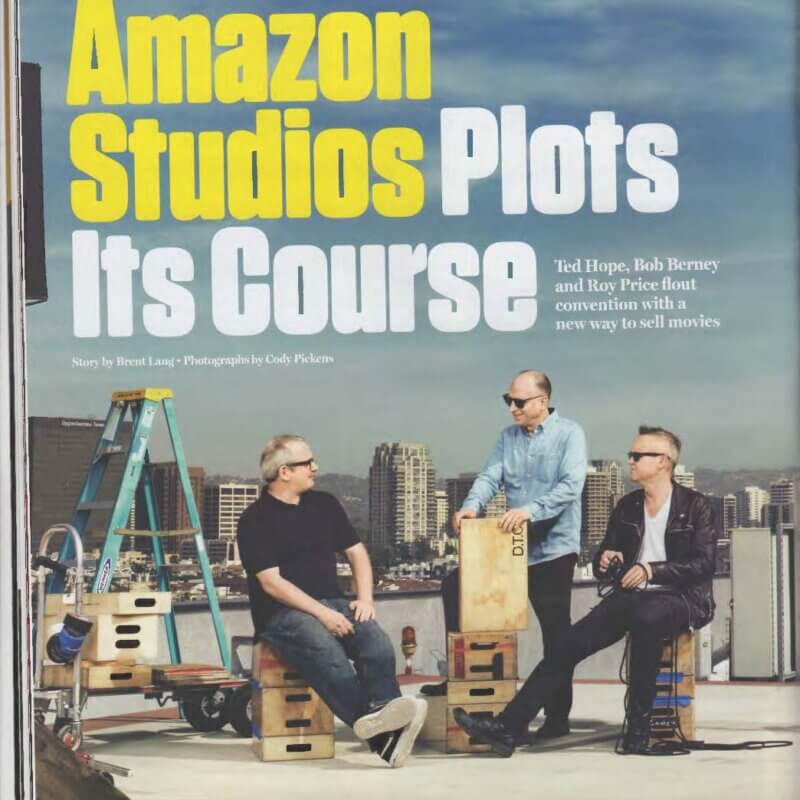

Amazon hopes to become a destination for the same kind of idiosyncratic artists on the film side, who may find themselves slightly to the left of mainstream tastes. To help realize his movie dreams, Price has tapped two film executives who had a front-row seat during the independent film revolution of the 1990s, Hope, producer of “The Ice Storm” and “American Splendor,’ and Bob Berney, former CEO of indie film distributor Picturehouse and the marketing guru behind “The Passion of the Christ” and “My Big Fat Greek Wedding,’ The hirings sent a clear message to filmmakers toiling in the arthouse scene.

“I don’t know who could have brought more credibility and knowledge and prestige to what they’re doing,” Stillman says. “There are not that many great homes for our kind of films, so it was hugely reassuring that this would be a place that could catapult them into the marketplace in the right way.”

For Hope, who was hired in January 2015, the call came when he was feeling disillusioned about the state of the movie business. In 2012, he took a job at the San Francisco Film Society, hoping to transform the nonprofit into an incubator for movies. But disagreements about funding led to his resignation the following year, and in a blistering op-ed on his website, he wrote that after working on more than 50 films, he was no longer interested in producing for a living. The economic model was collapsing, he wrote, and cobbling together financing required too many sacrifices – cuts in budgets and development time, and casting concessions to appease the money.

“I want to make films that lift the world and our culture higher – and our current way of doing things does just the opposite,” Hope wrote.

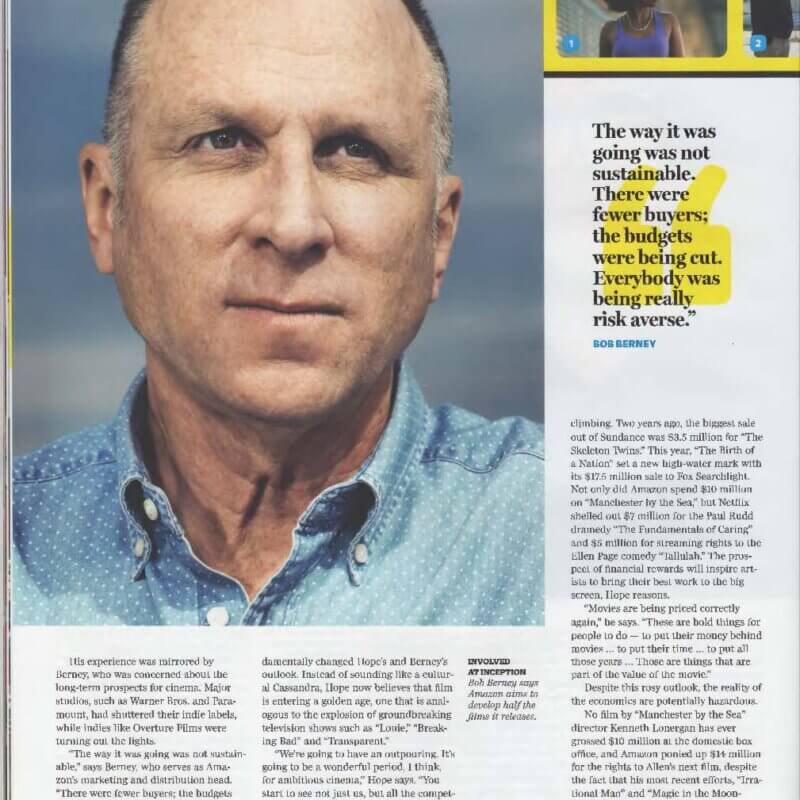

His experience was mirrored by Berney, who was concerned about the long-term prospects for cinema. Major studios, such as Warner Bros. and Paramount, had shuttered their indie labels, while indies like Overture Films were turning out the lights.

“The way it was going was not sustainable,” says Berney, who serves as Amazon’s marketing and distribution head. “There were fewer buyers, the budgets were being cut. Everybody was being really risk averse.”

Working at Amazon, which has the cash and the mandate to back films that aren’t scrubbed of their edges, has fun damentally changed Hope’s and Berney’s outlook. Instead of sounding like a cultural Cassandra, Hope now believes that film is entering a golden age, one that is analogous to the explosion of groundbreaking television shows such as “Louie,’ “Breaking Bad” and “Transparent.”

“We’re going to have an outpouring. It’s going to be a wonderful period, I think, for ambitious cinema,” Hope says. “You start to see not just us, but all the competitors that are out there, (enlist) different models where it makes sense to take bigger risks with films of great ambition.”

Part of the reason for his confidence is that the acquisition prices for films are climbing. Two years ago, the biggest sale out of Sundance was $3.5 million for “The Skeleton Twins,’ This year, “The Birth of a Nation” set a new high-water mark with its $17.5 million sale to Fox Searchlight. Not only did Amazon spend $10 million on “Manchester by the Sea,’ but Netflix shelled out $7 million for the Paul Rudd dramedy “The Fundamentals of Caring” and $5 million for streaming rights to the Ellen Page comedy ‘Tallulah,’ The prospect of financial rewards will inspire artists to bring their best work to the big screen, Hope reasons.

“Movies are being priced correctly again,” he says. “These are bold things for people to do – to put their money behind movies … to put their time … to put all those years … Those are things that are part of the value of the movie.”

Despite this rosy outlook, the reality of the economics are potentially hazardous.

No film by “Manchester by the Sea” director Kenneth Lonergan has ever grossed $10 million at the domestic box office, and Amazon ponied up $14 million for the rights to Allen’s next film, despite the fact that his most recent efforts, “Irrational Man” and “Magic in the Moonlight,’ collapsed in theaters.

That said, Amazon’s business is dramatically different than that of a traditional studio, which still needs a film to break even or make a profit through some combination of ticket sales, home entertainment rentals, and purchases. Amazon doesn’t measure success in box office. Price says he thinks in terms of movie slates, and isn’t concerned if a film marches into the black. With Amazon’s $271 billion market cap, losing a few million on a film won’t make a difference.

“I don’t focus on the individual movie making money,” Price says. “It’s the system that creates value as a whole.”

Making sense of how success is quantified is tricky. Amazon Prime doesn’t just offer its members television shows and films to stream. It is first and foremost a cheaper shipping service, guaranteeing two-day delivery for an annual subscription price of roughly $100. Just as movie theaters exist primarily as a vehicle to sell audiences popcorn, Amazon Prime’s reason for being is to get products to its customers faster. Price says there’s data to suggest that the films and shows Prime customers can access are a draw for them to sign up or renew their membership, but he doesn’t offer any specifics about how they correlate. Nor does he break down subscriber levels, although analysts estimate that Prime has roughly 50 million customers in the U.S.

“We have no idea how many of these subscribers are actually watching video,’ says Tim Mulligan, an analyst at Midia Research. “What we do know is, globally, Netflix is winning the battle. They’re in 190 territories worldwide. Amazon is in five. There’s a recognition that [Amazon needs] to up their game or risk being left behind.”

That kind of arms race requires a lot of cash. Netflix will shell out $5 billion in 2016, and while Amazon isn’t disclosing its programming budget, some analysts estimate it will spend more than $3 billion this year spread over its TV, music and film units. That dwarfs what a smaller distributor is able to spend, and figures to escalate as Amazon starts to develop and produce its own projects, instead of buying completed films at festivals. Amazon estimates that by 2017, at least half of the films it releases will be homegrown.

“The scope of the plan really requires that,’ Berney says. “To do 12-plus films a year, and to be able to expand to have a different outlook, different voices, you really have to have development for that kind of output.”

Of course, that carries risk. It means that Amazon is responsible for budget overruns or auteurs run amok. Just ask Paramount’s Evans, who was burned by Francis Ford Coppola’s attempts to recapture the magic of “The Godfather” on “The Cotton Club,’ or Harvey Weinstein, whose Miramax tenure was nearly derailed when costs spiraled on “Gangs of New York” and “Cold Mountain.”

Amazon’s money won’t be spent on perks. Like other Silicon Valley players, it can seem downright frugal. Instead of a gleaming tower or a sprawling studio lot, its film and television operations are housed several freeways removed from Hollywood, across three floors in a utilitarian Santa Monica building with an open office plan.

For his part, Price embraces the parsimony by making a point of flying coach on business trips.

“I walk by a lot of people in business class who are in this business,” he says. “It’s a small example, but philosophically, it’s meaningful. At the end of the day, the money should be spent on the movies and on things that customers care about.”